By Patti Johnson

By Patti Johnson

September 30, 2025

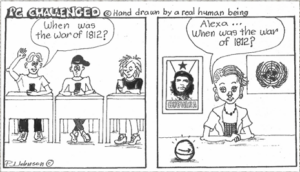

Unless we become Amish, (which is probably a healthier lifestyle), the mastery of technology is essential for success in the 21st century and should be taught in schools. This guest opinion is going to cover three areas where the use or overuse of technology is not beneficial to students and can be dangerous.

- 1. Overuse of technology can dumb down education increasing illiteracy and decreasing intelligent thought and brain capacity.

- Technology can be used to psychologically control and manipulate students.

- Recent tragedies have shown that AI has encouraged vulnerable youth to kill or commit suicide.

Technology in the classroom has evolved from calculators and spell check to every student with a laptop computer and smart phone, to Large Language Models (LLM’s) like ChatGPT and Grok. Will the final destination be human brain chip computer interfaces like Elon Musk’s Neuralink or Sam Altman’s venture Merge Labs?

Technology in the classroom has evolved from calculators and spell check to every student with a laptop computer and smart phone, to Large Language Models (LLM’s) like ChatGPT and Grok. Will the final destination be human brain chip computer interfaces like Elon Musk’s Neuralink or Sam Altman’s venture Merge Labs?

- Overuse of technology can dumb down education, increasing illiteracy and decreasing intelligent thought and brain capacity.

In 1982 Harvard Professor Anthony Oettinger, a member of the Council of Foreign Relations, gave a shocking speech to 52 telecom executives in which he outlined where he envisioned technology influencing education and literacy in the United States. In his speech titled “Regulated Competition in the United States.” he said,

“The present “traditional” concept of literacy has to do with the ability to read and write. Do we, for example, really want to teach people to do a lot of sums or write in a “fine round hand” when they have a five-dollar, hand-held calculator or a word processor to work with? Or do we really have to have everybody literate—writing and reading in the traditional sense—when we have the means through our technology to achieve a new flowering of oral communication? It is the traditional idea that says certain forms of communication, such as comic books, are “bad.” But in the modern context of functionalism, they may not be all that bad.” [1]

Technological advances have slowly been introduced into the classroom. Handheld calculators became available and affordable in the 1970’s. Parents and educators questioned whether calculators would have a negative effect on the foundational math skills of students in their early grades. They debated whether they would hinder the development of arithmetic abilities. According to the article, “A Brief History of Calculators in the Classroom” written in 2015, “Some forty years after the calculator first entered the classroom, these questions still have not been resolved” [2]

In 1975, the National Advisory Committee on Mathematical Education (NACOME) suggested that the calculator be used starting in eighth grade.

In 1980 the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) recommended calculators to be integrated at all grade levels.

I first became aware of the “calculator issue” in the 1980’s. In grade school our son did not have to memorize basic addition, subtraction and multiplication tables like I did as a child. Instead, he was handed a calculator.

There are problems with the method of “not” teaching foundational math skills of Arithmetic in early grades. When addition, subtraction and multiplication tables are memorized one can solve a basic math problem quicker than with a calculator. By the time it takes to enter the basic equation into a calculator, a student who has memorized his math tables can beat the machine to the answer. I have always appreciated my math training in the the1950’s which began by memorizing addition, subtraction and multiplication tables. After that, division problems were easy to accomplish quickly. At the grocery checkout I can usually add up my groceries in my head and know when I am not being charged correctly. (Of course, with more complicated problems, I do have to use a pencil and paper.) whereas most young checkers are at a loss when the power goes out. Same goes with calculating the change due when cash is used.

One problem with the quick or lazy fix of always referring to a tech device like a computer, calculator or smart phone for an answer is that it can be detrimental to brain development at any time in life, but especially in the early years when the brain is developing.[3]

Like a muscle that strengthens with exercise, the brain also strengthens through activities like learning and problem-solving. According to Neuroscientist Michael Merzeich, “Engaging in cognitively stimulating tasks can improve memory and processing speed, while disuse or lack of mental stimulation may lead to cognitive decline over time, as seen in conditions like age-related dementia.” In other words, use it or lose it! He also stated that “Mental challenges promote neuroplasticity, forming new neural connections and enhancing cognitive function.”[4]

I asked a Physics engineer his thoughts about early introduction of calculators in the classroom. He lamented the fact that he was not taught to memorize his basic math tables. He claimed that the use of calculators at an early age creates both a dependency and loss of confidence in our ability to do math without a device. He explained that he was taught conceptual math instead. Conceptual math is understanding the concept of math. He said that truth/rote memorization of math facts should be taught first, arguing that memorizing facts like addition and multiplication tables would have provided a foundation for understanding concepts easier.

In essence, educators threw the baby out with the bath water claiming that “all” rote memorization of facts is bad. Education should have a balance of both rote memorization and conceptual learning and should not replace one with the other. Only using rote memorization is bad and vice versa only using conceptual learning is equally wrong.

My subsequent encounter with early technology usage in education occurred when our son came home with assignments containing spelling and grammatical errors, yet he consistently received a big red “A” marked at the top. I wondered, “Why did he get an A?” It was obvious that he was not being taught spelling or grammar. I set up a meeting with his teacher and asked her why she did not have spelling lists, spelling tests or spelling bees. She replied that she did not need to teach spelling anymore because the children could now use spell check. Her answer was odd because her classroom did not even have computers. Even so, I explained to her that currently spell check could not even tell the difference between homophones and could inappropriately use the wrong word. Homophones are words that sound the same but are spelled differently. Some examples are: two, too and to, sea and see and there, their and they’re.

The teacher even had another excuse. She told me that with spelling bees only one person wins, and it hurts the other childrens self-esteem. I replied that our son won’t have self-esteem if he gets to college and can’t spell. I then said, “You’re not preparing students for the real world. The real world does not care about feelings. There are winners and losers. The smartest or most capable person gets the job. Children need to learn how to lose and then pick themselves up and work harder to succeed.”

The teacher then gave another reason for not teaching students to spell. She claimed that creative writing was more important and having to spell correctly would stifle their creativity. I replied that I was all for creative writing. Let them creatively write their essays then use the misspelled words as a teaching tool. Have the students rewrite the creative paper again but with the words spelled correctly. At this point she was flustered and irritated with my suggestions and asked me, “Do you have a teaching degree?” I replied, “No,” She then put her nose in the air and said, “Then leave the teaching up to us experts.”

At that time, many parents expressed concerns regarding the removal of spelling and phonics instruction from the curriculum. As more schools provide a laptop for every child and more students have cellphones, the elimination of learning to spell has increased. The debate is still going on today. [5] [6]

A multimedia lecturer bemoaned the way spell check in word processors had deteriorated his spelling ability. Not thinking or having to think about how a word was spelled eroded his ability to remember the correct spelling and the general rules of English grammar. Again, the phrase “use it (your brain) or lose it” applies.

Most schools have significantly reduced or eliminated cursive writing instruction in recent years. This is partly due to the adoption of the Common Core State Standards, which do not include cursive as a required skill. The increased focus is on computer keyboarding skills. While a few states and districts still teach cursive, many others have shifted their focus to technology. In these days of computers, smart phones and other smart data devices, fewer people write in cursive. Which is unfortunate because cursive writing helps develop the brain by “creating multi-sensory input and increasing neural pathways, which activates regions responsible for language, memory, and motor control. The intricate movements of cursive engage more brain areas than printing or typing, improving fine motor skills, and leading to better learning, retention, and overall cognitive function.” [7]

Today’s students read very few books. I first recognized this trend when our son was a freshman in high school. During his English class, students were assigned only one book to read throughout the entire academic year. But the teacher did manage to find time for the students to spend fifteen minutes meditating each morning in English class. I objected and had our son removed from that class. Traditionally, a common guideline for the number of books assigned during the school year corresponded with the student’s grade level. It seemed like the reduction of books was reminiscent of the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451.

© 2025 Patti Johnson – All Rights Reserved

E-Mail Patti Johnson: pj4charis@gmail.com

Footnotes:

[1] Charlotte Iserbyt The Deliberate Dumbing Down of America, A Chronological Paper Trail (Ravenna, Ohio, Conscience Press, 1999) pg. 183

[2] https://hackeducation.com/2015/03/12/calculators

[3] https://hackeducation.com/2015/03/12/calculators

[4] https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_merzenich_growing_evidence_of_brain_plasticity

[5] https://www.readabilitytutor.com/spelling-test/

[6] https://irrc.education.uiowa.edu/blog/2023/10/spelling-lists

[7] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4274624/