By Servando Gonzalez

By Servando Gonzalez

October 17, 2022

Several articles have appeared in the past weeks alleging that the present situation with Russia could become another Cuban Missile Crisis. Nevertheless, I will show below why I don’t think so.

According to common lore, the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 was a direct and dangerous confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War and was the moment when the two superpowers came closest to nuclear conflict. Nevertheless, the Cuban missile crisis is still a very elusive historical event. For sixty years it has captured the imagination of the media, scholars, and the public alike, producing a veritable mountain of articles, scholarly essays and books. Still, after so much effort by so many privileged minds, some aspects of the Cuban missile crisis continue to defy any logical explanation and are as puzzling today as they were at the time of the event. Below, I am going to study some of the alleged evidence of the presence of strategic missiles and their associated nuclear warheads in Cuba in 1962.

Is “Photographic Evidence” Evidence at All?

The official story offered by the Kennedy administration, and accepted at face value by most scholars of the Crisis and later popularized by the American mainstream media, is that though rumors about the presence of strategic missiles in Cuba had been widespread among Cuban exiles in Florida since mid-1962, the American intelligence community was never fooled by them. To American intelligence analysts, “only direct evidence, such as aerial photographs, could be convincing.”

It was not until Sunday, 14 October, 1962, that a U-2, authorized at last to fly over the Western part of Cuba, brought the first high-altitude photographs of what seemed to be Soviet strategic missile sites, in different stages of completion, deployed on Cuban soil.

Once the photographs were analyzed by experts at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC), they were brought to President Kennedy who, after a little prompting by a photo-interpreter who attended the meeting, accepted as a fact the NPIC’s conclusion that Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev had taken a fateful, aggressive step against the U.S. by placing nuclear-capable strategic missiles in Cuba. This meeting is considered by most scholars to be the beginning of the Cuban missile crisis.

Save for a few non-believers at the United Nations —a little more than a year before, U.S. Ambassador to the UN Adlai Stevenson had shown the very same delegates “hard” photographic evidence of Cuban planes, allegedly piloted by Castro’s defectors, which had attacked positions on the island previous to the Bay of Pigs landing, which later found to be fakes— most people, including the members of the American press, unquestionably accepted the U-2 photographs as evidence of Khrushchev’s treachery.

Beginning with Robert Kennedy’s classic analysis of the Crisis, the acceptance of the U-2’s photographs as hard evidence of the presence of Soviet strategic missiles deployed on Cuban soil has rarely been contested. CIA  director John McCone reaffirmed the same line of total belief in a Top Secret post-mortem memorandum of 28 February 1963 to the President. According to McCone, aerial photography was “our best means to establish hard intelligence.”

director John McCone reaffirmed the same line of total belief in a Top Secret post-mortem memorandum of 28 February 1963 to the President. According to McCone, aerial photography was “our best means to establish hard intelligence.”

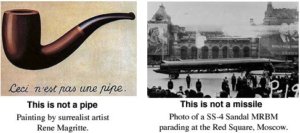

But both Robert Kennedy and John McCone were dead wrong. As Magritte’s picture The Treachery of Images masterly exemplifies, a picture of a pipe is not a pipe, and a picture of a missile is not a missile. A photograph of a UFO is not a UFO. Clint Eastwood was not Dirty Harry. Charlton Heston was not Moses. Tom Cruise is not a Naval Aviator. A picture, by itself alone, can hardly be accepted as “hard” evidence of anything. Linguist Alfred Korzybski masterly expressed it when he wrote, “The map is not the territory.” The fact is so obvious that no time should be wasted discussing it. It seems, however, that the very fact that it is so obvious —somebody said that the best way to hide something is by placing it in plain view— has precluded scholars from studying it in detail. Therefore, let’s analyze the obvious.

We are so used to dealing with photographs that most of the time we refer to them as if they were the real thing. A typical example is when a coworker pulls out of his wallet a photo of his family and says “this is my daughter, this is my wife, this is my dog, this is my house.” Of course, what you see in a photograph is not the real thing, just an image of the thing.

Missiles vs Images of Missiles

Most studies about the Cuban missile crisis repeat the extended opinion that the U-2 photographs were the hard, irrefutable evidence provided by the photo interpreters at the NPIC as the ultimate, incontrovertible proof that the Soviets had secretly deployed strategic missile bases in Cuba. But, in

order to become meaningful information, photographs need to be decoded (interpreted) by an

interpreter.

Being a subjective process, however, decoding is full of pitfalls. There is always the risk of aberrant decoding, by which a sign is interpreted as something totally different from what the creator of the sign originally intended to communicate. The process is known as aberrant decoding. In the case of the U-2 photographs, the NPIC photo interpreters incorrectly decoded the objects appearing in them as strategic missiles, instead of images of strategic missiles. But accepting the images of missiles as the ultimate proof of the presence of strategic missiles in Cuba was a big jump of their imagination, as well as a semantic mistake. A more truthful interpretation of the things whose images appeared in the U-2’s photographs would have been to describe them as “objects whose photographic image highly resemble the auxiliary equipment used in Soviet strategic missile bases.” But the photo interpreters at the NPIC confused —or rather felt forced to confuse— the images of the objects they saw in the photographs with the actual missiles. Afterwards, like mesmerized children, the media and the scholarly community have blindly followed the Pied Piper of photographic evidence. But, as in Magritte’s painting, a picture of a missile in not a missile.

With the advent of the new surveillance technologies pioneered with the U-2 plane and now extensively used by imaging satellites, there has been a growing trend in the U.S. intelligence community to rely more and more on imaging intelligence, now provided by satellites, and less and less on agents in the field (human intelligence, HUMINT). But, as any intelligence specialist can testify, photographs alone, though a very useful surveillance component, should never be passed as hard evidence. Photographs, at best, are just indicators pointing to a possibility which has to be physically confirmed by other means, preferably by trained, qualified agents working in the field.

Moreover, even disregarding the fact that photographs can be faked and doctored, nothing is so misleading as a photograph. According to the information available to this day, the photographic evidence of Soviet strategic missiles on Cuban soil was never confirmed by American agents working in the field. The highly quoted report of a qualified agent who saw something “bigger, much bigger” that anything the Americans had in Germany, omitted the important fact that what he actually saw was a canvas-covered object resembling a strategic missile. Actually, the missiles were never touched, smelled, or weighed. Their metal, electronic components, and fuel were never tested; the radiation from their nuclear warheads was never recorded; their heat signature was never verified.

According to philosopher Robert Nozick, the main criteria for considering a fact objective is that it is invariant under certain transformations, and he gives three characteristics that mark a fact as objective: First, “an objective fact must be accessible from different angles. Access to it can be repeated by the same sense (sight, touch, etc.), at different times; it can be repeated by different senses of the same observers. Different laboratories can replicate the phenomenon.” Second, “there is or can be intersubjective agreement about it.” Third, objective facts must hold “independently of people’s beliefs, desires, hopes, and observations or measurements.”

One of the golden rules of intelligence work is to treat with caution all information not independently corroborated or supported by reliable documentary or physical evidence. Yet, declassified Soviet documents, and questionable oral reports from Soviet officials who allegedly participated directly in the event, were accepted as sufficient evidence of the presence of strategic missiles and their nuclear warheads in Cuba in 1962. But one can hardly accept as hard evidence non-corroborated, nonevaluated information coming from a former adversary. Even if some day this becomes accepted practice in the historian’s profession, I can guarantee my readers that it will never be adopted in the intelligence field.

Photographs are just information, and information is not true intelligence until it has been thoroughly validated. As a rule, most counterintelligence analysts believe that only information that has been secretly taken from an opponent and turned over is bona fide intelligence. But, if the opponent had intended it to be turned over, it is automatically considered disinformation.

One of the principles of espionage work is that what is really important is not what you know, but that your opponent doesn’t know that you know. As CIA’s Sherman Kent pointed out, once the U-2 brought (what seemed to be) photographs of strategic missiles in Cuba, the main thing was to keep it secret. “Until the President was ready to act, the Russians must not know that we knew their secret.”

The fact that the Soviets had been so clumsy, failing to properly camouflage their missiles, surprised the American intelligence community. As it happens most of the time, however, American scholars found plausible explanations a posteriori for the Soviets’ behavior. These explanations ranged from flawed bureaucratic standard operating procedures to political-military disagreements, and pure and simple carelessness. Nevertheless, still today the fact constitutes one of the most unexplainable Soviet “mistakes” during the crisis. Probably one of the most known explanations was the one offered by scholar Graham T. Allison.

According to him, the failure to camouflage the missiles had a simple answer: bureaucratic procedures in the Soviet Army. Before the crisis, missile sites had never been camouflaged in the Soviet Union, so, the construction crews at the sites in Cuba did what they were used to doing, building missile sites according to the installation manuals, because somebody forgot to retrain them before they were sent to work in Cuba.

But, knowing the operational procedures of the Soviet Army, Allison’s explanation seems a bit too simplistic to be credible. First of all, the personnel assigned to do the job of building the missile sites were not common soldiers, but specially trained personnel. Secondly, even without disregarding the bureaucratic procedures common to all armies, it is a naive assumption to suppose that the Soviets could have made this type of gross mistake, particularly if they were trying to deploy the missiles in Cuba using deception and stealth, as the U.S. official version of the event claimed. Of course, this is only a variation of the “the-Russians-are-stupid” argument. This may also explain why the Soviet soldiers involved in Operation Anadyr (code name for the Cuban operation) were supplied with skis and cold weather gear and clothing before traveling to Cuba. But now we know that this was not because of an error, but part of the maskirovka designed to disguise the operation. According to U.S. intelligence sources, missile sites had never been camouflaged in the Soviet Union.

However, after Gary Power’s U-2 was shot down, the flow of information about Soviet missiles almost stopped completely. Aside from the fact that, being in the so-called “denied areas,” where no in situ verification by agents in the field was possible, we don’t know if the U-2 photos never detected camouflaged sites because the camouflage was so effective it avoided the missiles being detected. Also, there is the possibility that most of the missile sites photographed by the U-2s on Soviet territory had actually been decoys.

Also, one can safely assume that, after the Gary Powers U-2 was shot down in 1960 and the Russians discovered the high quality of its surveillance cameras, the Soviet Missile Forces would have changed their procedures and would have camouflaged their missile sites. Furthermore, Soviet military literature strongly emphasizes the importance of surprise (udivlenie) and deception (loz’n) in modern warfare.

Among it, the literature on camouflage (maskirovka), is particularly abundant. The Russian tradition of using camouflage to mislead goes back to the times of count Potemkin and the fake villages he ordered to build to fool Catherine the Great. Consequently, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, if the Soviet personnel in charge of installing the missiles failed to camouflage them, it was not because they were stupid, but because they were specifically ordered to do so.

The lack of adequate camouflage to hide the missiles from American observation is such a gross mistake that author Anatol Rappoport assumed that it was part of a Soviet plan by which the missile sites were meant to be discovered by American spy planes. During the height of the crisis, the Wall Street Journal reported that “the authorities here almost all accepted one key assumption: that Mr. Khrushchev must have assumed that his Cuban sites would soon be discovered.” The report also added that, according to one authority who had studied the photographic evidence, “The Russians seem almost to have gone out of their way to call attention to them.”

Similarly, the Cubans were aware of the quality of American air surveillance technology. In 1961, Life magazine published a report about the anti Castro guerrillas fighting in the Escambray mountains.

Some of the photographs illustrating the article had been taken by the U-2s. On several occasions Castro asked the Soviets to give him SAMs, and let his people operate them, but the Russians were reluctant. Although most of the Cubans assigned to the SAM bases were engineering students from the University of Havana, the Soviets only allowed them to operate the radars.

To the evidence offered above of the Soviets’ willingness to let the missiles be discovered, I can add some of my own. As a Cuban Army officer during the crisis I was assigned to headquarters and sent on inspection visits to several military units to assess their combat morale and battle readiness. One of these visits was to the Isle of Pines, where I visited a unit, deployed in an area close to the Siguanea peninsula, not far from a Soviet missile base located on the top of a nearby hill, not far from the coast.

The Cuban soldiers had aptly nicknamed the base “el circo soviético,” (the Soviet Circus), because of the canvas tarpaulins surrounding it. But the most interesting detail is that, though the tarps precluded observers from seeing the base from the ground, the base itself remained uncovered on top and in plain view to American spy planes. So, it seems that, though the Soviets apparently were eager to allow longdistance detection, they didn’t want any short-range observation of the missiles by the Cubans.

In another inspection I visited a Cuban Air Force base at San Antonio de los Baños, south of Havana. The visit occurred after president Kennedy had alerted the American public about the presence of missile bases in Cuba. Low-level American reconnaissance flights had begun, and Castro had ordered the antiaircraft batteries under his command to fire at American planes. Once at the base, we drove our jeep to the runway, where I saw in the distance several Mig fighter planes, which looked to me like MiG 15 or 17 models, lying like sitting ducks on the apron. On close inspection, however, we discovered that the planes were clumsy dummies made out of wood, cardboard and painted canvas. An officer at the base told us that the real planes were well protected and camouflaged.

As we were talking to other officers at the end of the runway, the antiaircraft batteries received a phone call telling them that American planes had entered Cuban airspace, and one of them was flying in our direction. A few minutes later, what seemed to me like a RF-101 Voodoo reconnaissance aircraft overflew us at treetop level, too fast for the inexperienced young soldiers manning the four-barreled

antiaircraft guns to open fire.

Though the dummies on the runway were perhaps good enough to fool the high-flying U-2s, they were too clumsily made to fool low-flying reconnaissance planes. The fact, however, that the Soviets had used decoy planes (and probably other types of decoys) in Cuba during the Crisis has never been mentioned in any of the U.S. declassified documents pertaining to the Crisis. Also, it is difficult to believe, to say the least, that Soviet maskirovka had worked so well on other aspects of the Cuban operation, but failed on the most important part of it: covering the strategic missile bases from prying American eyes. Therefore, there is a strong possibility that the missiles deployed in Cuba, like the ones Khrushchev was displaying in Moscow’s parades, were a ruse de guerre; nothing but empty dummies.

It is known that, after Gary Powers’ U-2 was shot down in May, 1960, the Soviets hurriedly began building dummy SAM silos. Dummy tanks, guns, and other types of war matériel were regularly deployed to confuse the sky spies. According to some sources, as late as 1960, even some units of the newly created Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces were not getting real missiles, but dummies.

Camouflage in warfare can be used either passively, to conceal from the enemy the true thing, or actively, to mislead the enemy into accepting a false one. From the point of view of semiotics, camouflage is intentional false encoding with the purpose of deceiving the decoder. Furthermore, in semiotic terms, camouflage can be defined as the art of confusing the enemy to make him believe that a sign of a thing is the thing itself, that is, to induce the enemy into magical thinking.

The case I have developed above is based on the unavoidable fact that even if the U-2 photos showed what looked like Soviet MRBMs in Cuba in 1962, photographic evidence alone cannot guarantee that real missiles were there. But now comes the most extraordinary thing about the alleged presence of strategic nuclear missiles in Cuban soil in 1962. High resolution copies of both the U-2 photos and the low-altitude photos taken later, are available on the internet for everybody to see. Nowhere in these photos, however, you can find anything resembling a Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile. The photos show no missiles at all!

What you can see, though, are some elongated objects covered by tarps, which we have been told are MRBMs, and some small concrete bunkers, which we have been told contained the nuclear warheads for the missiles. Of course, only Cold War true believers can take those claims as facts.

The photo interpreters at the NPIC allegedly had positively identified the missiles when they spotted what looked like tail fins sticking out under the tarpaulins. They were identical to the fins of the MRBMs they had photographed in Moscow in the may day parade that year. But, again, making a dummy of a box containing a missile is even easier than making a dummy of a missile.

So, you may use any name you want to name the present crisis with Russia. But, please, don’t call it another Cuban Missile Crisis. Vladimir Putin is not Nikita Khrushchev and Putin’s nuclear missiles are not dummies. Moreover, as any hunter can tell you, provoking a bear is not a good idea.

For a detailed analysis of the Cuban Missile Crisis you may read my book The Nuclear Deception: Nikita Khrushchev and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

© 2022 Servando Gonzales – All Rights Reserved

E-Mail Servando Gonzales: servandoglez05@yahoo.com