Edwin Vieira, JD., Ph.D.

Edwin Vieira, JD., Ph.D.

Recently, both the big “mainstream” media and hundreds of alternative sources on the Internet have overflowed with the opinions of commentators, pundits, bloggers, public officials at all levels of the federal system, retired military officers, sports stars, and assorted “celebrities”, concerning the authority (or lack thereof) of the President of the United States to intervene in the rampage of riots, looting, arson, and even killings which have plagued American cities following the homicide of Mr. George Floyd. The major lesson one learns from this palaver is that the writers and speakers generating it possess little to no real knowledge of the subject-matter, and apparently have no inclination to acquire any. That is both amazing and frightening. For, besides being of the highest importance, the subject-matter is so clear cut that anyone who has obtained a secondary-school education of the quality generally available prior to (say) 1970 should be able to understand it with a minimum of mental strain. The following points are intended to clarify the matter for anyone whose thinking needs clarification—

FIRST. Article II, Section 1, Clause 7 of the Constitution of the United States mandates that “[b]efore he enter on the Execution of his Office, [the President] shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:—‘I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.’” Everything which follows in this analysis comes within the purview of this “Oath”.

SECOND. Article II, Section 1, Clause 1 of the Constitution provides that “[t]he executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” That is, all “executive Power”, because the latter Clause recognizes no exceptions or exclusions.

THIRD. Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the Constitution provides that “[t]he President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States[.]” The Constitution recognizes no one other than the President as the recipient of this status and authority.

FOURTH. Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution requires that the President “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”. This is not only a duty, but also a power and a right (in the strict legal senses of those terms). Self-evidently, one manner of fulfilling this duty, and exercising this right and power, is for the President to take appropriate actions as “Commander in Chief” of the forces the Constitution places within his control.

FIFTH. Article I, Section 8, Clauses 15 and 16 of the Constitution delegate to Congress the power “[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, [and] suppress Insurrections”, whereupon “such Part of the[ Militia]” as may be “call[ed] forth” is considered to “be employed in the Service of the United States”.

SIXTH. Article I, Section 8, Clause 18 of the Constitution delegates to Congress the power “[t]o make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution” not only its own “Power[ ]” “[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia”, but also “all other Powers vested by th[e] Constitution in * * * any * * * Officer thereof”, such as the “Power[ ]” of the President to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”.

SEVENTH. Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution provides (in pertinent part) that “[n]o State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” And Section 5 of that Amendment provides that “[t]he Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

EIGHTH. Pursuant to its powers recited above, Congress enacted the present Section 252 of Title 10 of the United States Code:

Whenever the President considers that unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any State by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, he may call into Federal service such of the militia of any State, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to enforce those laws or to suppress the rebellion.

This is no novel contemporary piece of legislation, but derives from the Act of 29 July 1861, Chap. XXV, An Act to provide for the Suppression of Rebellion and Resistance to the Laws of the United States, and to amend the Act entitled “An Act to provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Law of the Union,” &c., passed February twenty-eight, seventeen hundred and ninety-five, 12 Stat. 281, and from the Act of 28 February 1795, Chap. XXXVI, An Act to provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions; and to repeal the Act now in force for those purposes, § 2, 1 Stat. 424, 424.

Section 252, apparently, is what people who pontificate about the President’s authority are calling “The Insurrection Act”. If so, the contention of critics that President Trump cannot rely upon this statute is balderdash—inasmuch as Presidents before him have invoked it successfully, with no widespread (or, really, any significant) outcry against the legality of their actions. See Executive Order No. 10730, 24 September 1957, 22 Federal Register 7628 (President Eisenhower); Executive Order No. 11053, 30 September 1962, 27 Federal Register 9681 (President Kennedy); Executive Order No. 11111, 11 July 1963, 28 Federal Register 5709 (President Kennedy); Executive Order No. 11118, 10 September 1963, 28 Federal Register 9863 (President Kennedy).

NINTH. Although 10 U.S.C. § 252 could apply under some circumstances to some of the disorders which have occurred in various States in recent days, it is not the statute which President Trump—were he well advised—should invoke to deal with the generality of riots, looting, arson, and even killings which Americans in those places have suffered. The statute which better fits the situation is the present Section 253 of Title 10 of the United States Code:

The President, by using the militia * * * shall take such measures as he considers necessary to suppress, in a State, any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy, if it—

(1) so hinders the execution of the laws of that State, and of the United States within the State, that any part or class of its people is deprived of a right, privilege, immunity, or protection named in the Constitution and secured by law, and the constituted authorities of that State are unable, fail, or refuse to protect that right, privilege, or immunity, or to give that protection; or

(2) opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.

In any situation covered by clause (1), the State shall be considered to have denied the equal protection of the laws secured by the Constitution.

This, too, is no novel contemporary piece of legislation, but derives from the Act of 20 April 1871, chap. XXII, An Act to enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other Purposes, § 3, 17 Stat. 13, 14. And its terms exactly describe the situation in those States in which civil unrest has broken out in recent days—namely, that “insurrection[s], domestic violence, unlawful combination[s], or conspirac[ies]” have terrorized the peaceful inhabitants, and “the constituted authorities of th[ose] State[s] are unable, fail, or refuse to protect th[e] right[s], privilege[s], immunit[ies], or to give the protection named in the Constitution and secured by law” for some “part[s] or class[es] of [those States’] people.

TENTH. Section 253 imposes no limits on the legal, let alone the commonplace, definitions of “insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” to which it applies. And the rioting, looting, arson, and killings which have taken place in various States surely fall within any acceptable definitions of those words.

ELEVENTH. Section 253 imposes no limit on what “militia” (or part thereof) the President may “us[e]”, so long (obviously) as that “militia” is recognized as such (i) by the Constitution itself—namely, “the Militia of the several States” (Article II, Section 2, Clause 1); or (ii) by a law of Congress which refers to some “Part of the[ Militia of the several States]” which “may be employed in the Service of the United States” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 16).

And pursuant to Article I, Section 8, Clauses 15, 16, and 18 of the Constitution, for “employ[ment] in the Service of the United States” in aid of “execut[ing] the Laws of the Union, [and] suppress[ing] Insurrections” (among other responsibilities), Congress has defined “[t]he militia of the United States” as follows:

(a) The militia of the United States consists of all able-bodied males at least 17 years of age and, [with certain exceptions not relevant here], under 45 years of age who are, or who have made a declaration of intention to become, citizens of the United States and of female citizens of the United States who are members of the National Guard.

(b) The classes of the militia are—

(1) the organized militia, which consists of the National Guard and the Naval Militia; and

(2) the unorganized militia, which consists of the members of the militia who are not members of the National Guard or the Naval Militia.

10 U.S.C. § 246.

TWELFTH. Section 253 imposes no limits on “the measures” that the President may “consider[ ] necessary to suppress, in a State, any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” to which that statute is addressed. So his statutory authority must include “using the militia” (as defined in 10 U.S.C. § 246) “to execute [whatever] Laws of the Union” may apply to the situation (which authority and responsibility the Constitution explicitly assigns to the Militia in Article I, Section 8, Clause 15 of the Constitution), so as to fulfill his duty to “take Care that th[os]e Laws be faithfully executed” (under Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution).

THIRTEENTH. As Section 253 provides, should the President determine that “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy * * * so hinders the execution of the laws of [a] State, and of the United States within th[at] State, that any part or class of its people is deprived of a right, privilege, immunity, or protection named in the Constitution and secured by law, and the constituted authorities of that State are unable, fail, or refuse to protect that right, privilege, or immunity, or to give that protection”, he may “consider” that “the State * * * ha[s] denied the equal protection of the laws secured by the Constitution.” In that regard, Section 253 is especially “appropriate legislation” through which Congress has empowered the President to “enforce” in the first instance the requirement that no State shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”, perforce of Sections 1 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. See the origin of 10 U.S.C. § 253 in Act of 20 April 1871, chap. XXII, An Act to enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other Purposes, § 3, 17 Stat. 13, 14.

For instance, the President could determine that, in those States in which riots, looting, arson, and homicide have taken place with no adequate response from public officials—or, even worse, with their tacit acquiescence or approval—“part[s] or class[es] of [those States’] people” have been deprived of the rights to “property” and even “life” “named in the Constitution”, as well as the immunities “secured by law” from, for example, riots (18 U.S.C. § 2101), insurrections (18 U.S.C. § 2383), and sedition (18 U.S.C. § 2384).

To this, no disgruntled State or Local official (or anyone else, for that matter) can offer a legal objection, whether under the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution or otherwise. After all, Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment delegates to Congress a plenary supervisory power which it may wield in aid of Section 1 of that Amendment against the States perforce of Article VI, Clause 2 of the Constitution (“the Supremacy Clause”). Under the Supremacy Clause, Sections 1 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, along with 10 U.S.C. § 253, are “the supreme Law of the Land” by which “the Judges in every State shall be bound * * * , any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” And, as required by Article VI, Clause 3 of the Constitution, “the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers * * * of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support th[e] Constitution” in the foregoing regard, not to disregard let alone to defy it.

FOURTEENTH. Inasmuch as Section 253 reaches every “insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” which comes within its terms, the President need not deal solely with the rioters, looters, arsonists, insurrectionists, and killers to be found at the scenes of their crimes, but may also search out organizers, agitators and propagandists, logisticians, intermediaries, financiers, and other accomplices of any sort who have escaped to or who have always performed their nefarious operations in distant places. And the President’s authority in this regard embraces not only individuals, but also all ostensibly legitimate “foundations”, “think tanks”, and like institutions which fund, otherwise support, or encourage such criminal misbehavior.

FIFTEENTH. As appears on its face, Section 253 does not require the President to solicit or receive the approval of a State’s Legislature, Governor, or other official before he (the President) executes that statute in that State. In this respect, Section 253 differs from 10 U.S.C. § 251. See the origin of § 251 in the Act of 28 February 1795, Chap. XXXVI, An Act to provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions; and to repeal the act in force for those purposes, § 1, 1 Stat. 424, 424.

SIXTEENTH. Were the Constitution and 10 U.S.C. § 253 by themselves not enough to drive the point home, the Supreme Court has in principle already opined that the President’s determinations under that statute must be accepted as conclusive by everyone else, including the Judiciary.

Pursuant to its constitutional power “[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia * * * to repel Invasions”, in 1795 Congress enacted legislation which provided in pertinent part

[t]hat whenever the United States shall be invaded, or be in imminent danger of invasion from any foreign nation or Indian tribe, it shall be lawful for the President of the United States to call forth such number of the militia of the state, or states, most convenient the place of danger, or scene of action, as he may judge necessary to repel such invasion, and to issue his orders for that purpose, to such officer or officers of the militia, as he shall think proper.

Act of 28 February 1795, Chap. XXXVI, An Act to provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions; and to repeal the act in force for those purposes, § 1, 1 Stat. 424, 424.

Referring to the power so delegated by Congress to the President, the Supreme Court described it as

not a power which can be executed without a corresponding responsibility. It is, in its terms, a limited power, confined to cases of actual invasion, or of imminent danger of invasion. If it be a limited power, * * * by whom is the exigency to be judged of and decided? Is the president the sole and exclusive judge whether the exigency has arisen, or is it to be considered as an open question * * * ? We are all of opinion, that the authority to decide whether the exigency has arisen, belongs exclusively to the president, and that his decision is conclusive upon all other persons.

* * * * *

If we look at the language of the act of 1795, * * * [t]he power itself is confided to the executive of the Union, to him who is, by the constitution, “the commander in chief of the militia, when called into the actual service of the United States,” whose duty it is to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” and whose responsibility for an honest discharge of his official obligations is secured by the highest sanctions. He is necessarily constituted the judge of the existence of the exigency in the first instance, and is bound to act according to his belief of the facts. If he does so act, and decides to call forth the militia, his orders for this purpose are in strict conformity with the provisions of the law; and it would seem to follow as a necessary consequence, that every act done by a subordinate officer, in obedience to such orders, is equally justifiable. The law contemplates that, under such circumstances, orders shall be given to carry the power into effect; and it cannot, therefore, be a correct inference, that any other person has a just right to disobey them. The law does not provide for any appeal from the judgment of the president, or for any right in subordinate officers to review his decision, and in effect defeat it. Whenever a statute gives a discretionary power to any person, to be exercised by him, upon his own opinion of certain facts, it is a sound rule of construction, that the statute constitutes him the sole and exclusive judge of the existence of those facts.

Martin v. Mott, 25 U.S. (12 Wheaton) 19, 29-32 (1827) (Story, J., for the Court).

This legal analysis applies directly, and with decisive effect, to 10 U.S.C. § 253—

(i) Congress enacted the Act of 1795 pursuant to its power in Article I, Section 8, Clause 15 “[to] provide for calling forth the Militia to * * * repel Invasions”. That very same Clause also authorizes Congress “[t]o provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, [and] suppress Insurrections”. Self-evidently, the principles Martin v. Mott invoked are equally applicable to all of the purposes for which the Militia may be called forth.

(ii) The Act of 1795 empowered the President “to call forth such number of the militia * * * as he may judge necessary”, and “to issue his orders for that purpose, to such officer or officers of the militia, as he shall think proper”. In like wise, 10 U.S.C. § 253 delegates to the President the broad authority “by using the militia * * * [to] take such measures as he considers necessary”. Thus, the latter statute is entitled to the same construction Martin v. Mott applied to the former one—namely, that “the authority to decide whether the exigency has arisen, belongs exclusively to the president, and * * * his decision is conclusive upon all other persons”; and “that, under such circumstances, orders shall be given to carry the power into effect”, and no “other person has a just right to disobey them.” Indeed, as applied to 10 U.S.C. § 253, the principles of Martin v. Mott should extend far beyond the facts of that case. For there the President’s power could be directed only at actual members of the Militia; whereas, under Section 253, “such measures as [the President] considers necessary” are not confined to members of the Militia alone, but instead may reach essentially anyone and everyone whose behavior is in any way implicated, for good or for bad, in the “insurrection[s], domestic violence, unlawful combination[s], or conspirac[ies]” those “measures” are designed “to suppress”.

(iii) Martin v. Mott held that the Act of 1795 “d[id] not provide for any appeal from the judgment of the president, or for any right in subordinate officers to review his decision, and in effect defeat it”—whether through their own unaided efforts or by importuning the Judiciary to interject itself into the matter on their behalf (which the Supreme Court refused to do in that case). Neither does 10 U.S.C. § 253 “provide for any [such] appeal” or “right * * * to review” for a member of “the militia of the United States” called forth under the aegis of that statute. The modern-day Supreme Court has recognized that the Judiciary may not interfere with the President’s enforcement of discipline within the Militia. See Gilligan v. Morgan, 413 U.S. 1, 5-12 (1973). And other persons affected by the President’s “measures” are no better off. For whereas under the Act of 1795 the President’s power extended only to actual members of the Militia, under 10 U.S.C. § 253 “such measures as [the President] considers necessary” are not confined to members of the Militia alone, but instead may reach essentially anyone and everyone whose behavior is in any way involved in the perpetration of “insurrection[s], domestic violence, unlawful combination[s], or conspirac[ies]”.

(iv) In reference to the Act of 1795, Martin v. Mott observed that “[w]henever a statute gives a discretionary power to any person, to be exercised by him, upon his own opinion of certain facts, * * * the statute constitutes him the sole and exclusive judge of the existence of those facts.” No less than that Act, 10 U.S.C. § 253 delegates an equally “discretionary power” to the President to “take such measures as he considers necessary”. That being so, the President’s exercise of that power cannot be second-guessed by the Judiciary for any reason whatsoever. For “[t]he province of the court is, solely, to decide on the rights of individuals, not to enquire how the executive, or executive officers, perform duties in which they have a discretion. Questions in their nature political, or which are, by the constitution and laws, submitted to the executive, can never be made in this court.” Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 170 (1803) (Marshall, C.J., for the Court).

(v) And Martin v. Mott is not alone in this regard. As the Supreme Court held in Nishimura Ekiu v. United States,

the final determination of * * * facts may be entrusted by Congress to executive officers; and in such a case, * * * in which a statute gives a discretionary power to an officer, to be exercised by him upon his own judgment of certain facts, he is made the sole and exclusive judge of the existence of those facts, and no other tribunal, unless expressly authorized by law to do so, is at liberty to reëxamine or controvert the sufficiency of the evidence on which he acted.

142 U.S. 651, 660 (1892), citing inter alia Martin v. Mott, 25 U.S. (12 Wheaton) 19, 31 (1827), and followed in Lem Moon Sing v. United States, 158 U.S. 538, 544 (1895).

(v) Finally, no matter how deeply “the Deep State’s” friends on the Bench despise President Trump and how desperately they desire to thwart him at every turn, unless and until the Supreme Court overrules Martin v. Mott the lower courts are required to adhere to its reasoning “no matter how misguided the judges of those courts may think it to be”. Hutto v. Davis, 454 U.S. 370, 375 (1982). Within the Judiciary, only the Supreme Court can overrule its own precedents. E.g., Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477, 484 (1989); Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203, 237 (1997); State Oil Company v. Khan, 522 U.S. 3, 20 (1997).

IN SUM, those people who vociferously contend that the President has no authority to suppress the kinds of riots, looting, arson, and killings going on within the States these days know not whereof they speak. And if plain ignorance is not the explanation for their behavior, what is?

© 2020 Edwin Vieira – All Rights Reserved

E-Mail Edwin Vieira: edwinvieira@gmail.com

Joan Swirsky

Joan Swirsky 21st CENTURY DEMOCRAT RACISM

21st CENTURY DEMOCRAT RACISM Lloyd Marcus

Lloyd Marcus By Allan Wall

By Allan Wall By: Devvy

By: Devvy So-called elective surgeries in some counties are suspended, again. Hospitals sit empty across the country from this kind of panic. People can’t get cancer and other types of testing or surgery that IS necessary for them but not considered important by Abbott and his medical ‘advisers’.

So-called elective surgeries in some counties are suspended, again. Hospitals sit empty across the country from this kind of panic. People can’t get cancer and other types of testing or surgery that IS necessary for them but not considered important by Abbott and his medical ‘advisers’. By Cliff Kincaid

By Cliff Kincaid By Frosty Wooldridge

By Frosty Wooldridge If the mayor of Seattle, Washington thinks thugs, anarchists and Antifa want to bring a “Summer of Love” into her streets, she’s in for a rude awakening. Already, one killed and another wounded in her “CHOP” section of downtown!

If the mayor of Seattle, Washington thinks thugs, anarchists and Antifa want to bring a “Summer of Love” into her streets, she’s in for a rude awakening. Already, one killed and another wounded in her “CHOP” section of downtown! By Marilyn M. Barnewall

By Marilyn M. Barnewall by Rev. Austin Miles

by Rev. Austin Miles The same manifesto says all churches must come down. Not only in America but around the world since religion “is the opiate of the people” and must be torn down.

The same manifesto says all churches must come down. Not only in America but around the world since religion “is the opiate of the people” and must be torn down. Roger Anghis

Roger Anghis Michael Heath

Michael Heath By Sidney Secular

By Sidney Secular Bradlee Dean

Bradlee Dean By: Amil Imani

By: Amil Imani Dave Daubenmire

Dave Daubenmire By Lee Duigon

By Lee Duigon By Jim Kouri – Senior Political News Writer

By Jim Kouri – Senior Political News Writer Obama, Valerie Jarrett (born in Iran), Susan Rice and other members of the former President’s inner-circle “systematically disbanded” special law enforcement units throughout the federal government that were investigating the Iranian, Syrian, and Venezuelan terrorism financing networks. Obama and his Secretary of State John Kerry were concerned the counter-terrorism units would lead to Iranian officials walking away from Obama’s precious nuclear deal with Iran, according to a former U.S. official with expertise in dismantling criminal financial networks

Obama, Valerie Jarrett (born in Iran), Susan Rice and other members of the former President’s inner-circle “systematically disbanded” special law enforcement units throughout the federal government that were investigating the Iranian, Syrian, and Venezuelan terrorism financing networks. Obama and his Secretary of State John Kerry were concerned the counter-terrorism units would lead to Iranian officials walking away from Obama’s precious nuclear deal with Iran, according to a former U.S. official with expertise in dismantling criminal financial networks Republican leaders of the House Committee initiated a full-scale investigation into the Obama administration’s activities getting a nuclear deal many believed was a farce at best, a deadly mistake at worst. They are also probing Obama’s controversial prisoner swap with Iran that included over a

Republican leaders of the House Committee initiated a full-scale investigation into the Obama administration’s activities getting a nuclear deal many believed was a farce at best, a deadly mistake at worst. They are also probing Obama’s controversial prisoner swap with Iran that included over a

By Ron Ewart

By Ron Ewart It seems like all you have to do is to steal everything in site, burn down blocks and blocks of buildings, take over a section of a city, harass and beat up some innocent bystanders and kill a few cops and you can get whatever you want, as other Americans and politicians bow to the pressure and intimidation of wanton violence. You can get the law changed, gut the police force, tear down some statues and get a new holiday. We already have Martin Luther King Day and Black History Month. Do we have to grant another national holiday to the black race (Juneteenth) to get them to stop tearing the country apart? That is bowing to the bully and we all know how that turns out. The bully enslaves us.

It seems like all you have to do is to steal everything in site, burn down blocks and blocks of buildings, take over a section of a city, harass and beat up some innocent bystanders and kill a few cops and you can get whatever you want, as other Americans and politicians bow to the pressure and intimidation of wanton violence. You can get the law changed, gut the police force, tear down some statues and get a new holiday. We already have Martin Luther King Day and Black History Month. Do we have to grant another national holiday to the black race (Juneteenth) to get them to stop tearing the country apart? That is bowing to the bully and we all know how that turns out. The bully enslaves us. Jake MacAulay

Jake MacAulay by Kathleen Marquardt

by Kathleen Marquardt Kelleigh Nelson

Kelleigh Nelson beauty supply houses, politicians, Hollywood elites, sports figures and others are caving to the totalitarian Marxists because they don’t want to be called racist. They are taking a knee to the anarchists of BLM.

beauty supply houses, politicians, Hollywood elites, sports figures and others are caving to the totalitarian Marxists because they don’t want to be called racist. They are taking a knee to the anarchists of BLM. Yet for all the MSM condemnation and vilifying of the president, nothing was said about the photo op of Democrats kneeling for eight minutes and 46 seconds in the Capitol Visitor Center. And to make it worse, they donned Ghana/Nigerian Kente cloth tapestries around their necks and masks to honor career criminal George Floyd who was killed by a police officer. They were

Yet for all the MSM condemnation and vilifying of the president, nothing was said about the photo op of Democrats kneeling for eight minutes and 46 seconds in the Capitol Visitor Center. And to make it worse, they donned Ghana/Nigerian Kente cloth tapestries around their necks and masks to honor career criminal George Floyd who was killed by a police officer. They were  When the FBI takes a knee to support BLM they are

When the FBI takes a knee to support BLM they are  Sure, black lives matter! But every other life matters too, and you never see BLM at abortion clinics. It’s okay to murder millions upon millions of black babies in their mothers’ wombs, but that’s not what BLM cares about despite the fact that

Sure, black lives matter! But every other life matters too, and you never see BLM at abortion clinics. It’s okay to murder millions upon millions of black babies in their mothers’ wombs, but that’s not what BLM cares about despite the fact that  BLM’s Radical Marxist Founders

BLM’s Radical Marxist Founders Obama and Mandela

Obama and Mandela Really President Obama? You drew inspiration from an avowed communist who destroyed South African white farmers who now have to live in protected communities, in order to keep from being slaughtered? You revere the rape and slaughter of pregnant women and children and their farmer fathers hacked to death by Mandela’s black forces? Apparently so, and we know your words have inflamed those who hate America’s whites and are destroying their property today.

Really President Obama? You drew inspiration from an avowed communist who destroyed South African white farmers who now have to live in protected communities, in order to keep from being slaughtered? You revere the rape and slaughter of pregnant women and children and their farmer fathers hacked to death by Mandela’s black forces? Apparently so, and we know your words have inflamed those who hate America’s whites and are destroying their property today. “Around the globe, Nelson Mandela is held up as an icon of justice, equality, and peaceful struggle for right. The problem with this image, however, is that it is entirely false. The record demonstrates beyond a shadow of a doubt that Nelson Mandela was not a peace-loving Freedom fighter, but a communist revolutionary who reveled in violence, promoted white genocide, and facilitated the Marxist subversion of South Africa.

“Around the globe, Nelson Mandela is held up as an icon of justice, equality, and peaceful struggle for right. The problem with this image, however, is that it is entirely false. The record demonstrates beyond a shadow of a doubt that Nelson Mandela was not a peace-loving Freedom fighter, but a communist revolutionary who reveled in violence, promoted white genocide, and facilitated the Marxist subversion of South Africa. Paul Cappadona

Paul Cappadona absolutely stereotyping doncha know. Has anyone else ever had the feeling that this world is one big insane asylum? If any other walls are put up around our country, they should be made of rubber. Instead of police, perhaps we should be patrolled by therapists. That might solve a lot of problems.

absolutely stereotyping doncha know. Has anyone else ever had the feeling that this world is one big insane asylum? If any other walls are put up around our country, they should be made of rubber. Instead of police, perhaps we should be patrolled by therapists. That might solve a lot of problems. Rob Pue

Rob Pue By J.W. Bryan

By J.W. Bryan Shirley Edwards

Shirley Edwards By Ron Edwards

By Ron Edwards Dave Daubenmire

Dave Daubenmire Butch Paugh

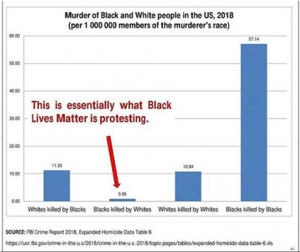

Butch Paugh Some people, especially the news media, Black Lives Matter, academics and socialist Democrat politicians, would construe and have construed from this that the cops are racists. However, one could also conclude that blacks perpetrate crimes at a higher rate than whites and are more than likely to come in contact with police, or arrested, or shot by police. Given the evidence, the latter is much more likely than the former.

Some people, especially the news media, Black Lives Matter, academics and socialist Democrat politicians, would construe and have construed from this that the cops are racists. However, one could also conclude that blacks perpetrate crimes at a higher rate than whites and are more than likely to come in contact with police, or arrested, or shot by police. Given the evidence, the latter is much more likely than the former. its citizens. Major events in Shi’a Islam was only celebrated during certain days of the year. These innocent and naïve Iranians had a completely imaginary and unrealistic vision of Islam without the slightest idea what the real Islam was, what the Qur’an said, what the Prophet of Islam did and did not do. Irrespective of any and all, they attributed Islam with their own vision, fantasy, ideals and beliefs. In other words, Islam was only as good as the person practicing it.

its citizens. Major events in Shi’a Islam was only celebrated during certain days of the year. These innocent and naïve Iranians had a completely imaginary and unrealistic vision of Islam without the slightest idea what the real Islam was, what the Qur’an said, what the Prophet of Islam did and did not do. Irrespective of any and all, they attributed Islam with their own vision, fantasy, ideals and beliefs. In other words, Islam was only as good as the person practicing it. forced these leaches to run and hide to the four corners of Iran and elsewhere. But his son, the

forced these leaches to run and hide to the four corners of Iran and elsewhere. But his son, the  Iranians are very proud people. All they are asking is that people and countries that are at clear risk from the mullahs ought to step up to the plate and help the Iranians, in numerous effective ways to get rid of these usurpers, these religious fanatics who are hell-bent on promoting their deadly agenda.

Iranians are very proud people. All they are asking is that people and countries that are at clear risk from the mullahs ought to step up to the plate and help the Iranians, in numerous effective ways to get rid of these usurpers, these religious fanatics who are hell-bent on promoting their deadly agenda. Edwin Vieira, JD., Ph.D.

Edwin Vieira, JD., Ph.D. By Greg Holt

By Greg Holt parties have heavily armed thugs only allowing inside the stupid and gullible? Inside an area where anarchists have taken over public property (police precinct) and are taunting police to do anything about it.

parties have heavily armed thugs only allowing inside the stupid and gullible? Inside an area where anarchists have taken over public property (police precinct) and are taunting police to do anything about it. The Founder of Blue Line Bears Is Broken as She Recognizes That the World Hates Her Dad Just for The Uniform That He Wears.

The Founder of Blue Line Bears Is Broken as She Recognizes That the World Hates Her Dad Just for The Uniform That He Wears. Mary Tocco

Mary Tocco So that rogue cop who killed Floyd immediately identified him as a counterfeiter even though there was no printing press anywhere in the area. However, for that particular cop, Floyd was guilty because, well, he was black.

So that rogue cop who killed Floyd immediately identified him as a counterfeiter even though there was no printing press anywhere in the area. However, for that particular cop, Floyd was guilty because, well, he was black. Laurie Roth

Laurie Roth Islam says that Allah is the javaab-ul-doaa (answerer of supplications/prayers) and that to him we should supplicate for any and all help in all matters.

Islam says that Allah is the javaab-ul-doaa (answerer of supplications/prayers) and that to him we should supplicate for any and all help in all matters. The list of my questions is long indeed. Here are some of my questions, not necessarily in order of importance, presented in all meekness to Allah, the Lord of Islam. To me, all questions are important and assigning relative importance to them is arbitrary. So, I get started.

The list of my questions is long indeed. Here are some of my questions, not necessarily in order of importance, presented in all meekness to Allah, the Lord of Islam. To me, all questions are important and assigning relative importance to them is arbitrary. So, I get started. A follow up question! Why a supremely august being, as you are, with all the indescribably exulted powers and attributes, chose an illiterate Arab, a hired-hand of a rich widow, as your messenger is a mystery. Couldn’t you have chosen a Rabbi from nearby Medina, a Zoroastrian Mobed (priest), a Christian Priest from Mecca itself, a Hindu Monk, a Buddhist Clergy? These were people who had specialized in matters of religion, rather than an Arab whose only skill was helping drive caravans of camels.

A follow up question! Why a supremely august being, as you are, with all the indescribably exulted powers and attributes, chose an illiterate Arab, a hired-hand of a rich widow, as your messenger is a mystery. Couldn’t you have chosen a Rabbi from nearby Medina, a Zoroastrian Mobed (priest), a Christian Priest from Mecca itself, a Hindu Monk, a Buddhist Clergy? These were people who had specialized in matters of religion, rather than an Arab whose only skill was helping drive caravans of camels. later banned GWTW throughout the Soviet Empire. Scarlett O’Hara was not a fan of war, and that made her dangerous. Now, the Democrats want to join with the Nazis and Communists to ban the Pulitzer Prize winning novel, GWTW. What does that tell you?

later banned GWTW throughout the Soviet Empire. Scarlett O’Hara was not a fan of war, and that made her dangerous. Now, the Democrats want to join with the Nazis and Communists to ban the Pulitzer Prize winning novel, GWTW. What does that tell you? the incoming wealth. Mitchell drove an old car and wore four year old cotton dresses. Instead of spending the money on herself, she used it wisely to help other people.

the incoming wealth. Mitchell drove an old car and wore four year old cotton dresses. Instead of spending the money on herself, she used it wisely to help other people. Battle Flag of Northern Virginia

Battle Flag of Northern Virginia Steven Yates

Steven Yates The Coming Civil War II?

The Coming Civil War II? Gov. Jindal spoke in Washington, D.C, at the annual Faith and Freedom Coalition conference.

Gov. Jindal spoke in Washington, D.C, at the annual Faith and Freedom Coalition conference. The bullet purchases drew widespread attention as the web site Infowars.com published several stories on them that were linked off the widely read Drudge Report and other sites.

The bullet purchases drew widespread attention as the web site Infowars.com published several stories on them that were linked off the widely read Drudge Report and other sites. George Lujack

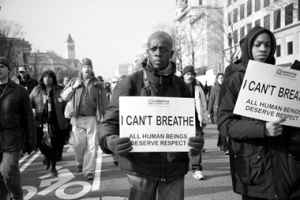

George Lujack head. There was no resistance. The man pleaded that he could not breathe. The neck restraint DID cause the death of George Floyd. If it did not cause strangulation or asphyxiation, it caused him to die of other health related issues. Without that 8 minute and 48 second neck restraint administered on George Floyd until he was unconscious, and after as he remained unconscious, he would surely be alive.

head. There was no resistance. The man pleaded that he could not breathe. The neck restraint DID cause the death of George Floyd. If it did not cause strangulation or asphyxiation, it caused him to die of other health related issues. Without that 8 minute and 48 second neck restraint administered on George Floyd until he was unconscious, and after as he remained unconscious, he would surely be alive. mean to protect and serve only the law-abiding community, but to protect and serve the lowest element persons in the communities that they serve as well. An arrestee with a substance abuse issue should be arrested and treated with dignity as a human being. Many cops believe that they have the right to “street justice,” to inflict pain upon in-custody,low-life prisoners. They don’t.

mean to protect and serve only the law-abiding community, but to protect and serve the lowest element persons in the communities that they serve as well. An arrestee with a substance abuse issue should be arrested and treated with dignity as a human being. Many cops believe that they have the right to “street justice,” to inflict pain upon in-custody,low-life prisoners. They don’t. If this scene had not been clearly recorded by cell phone, George Floyd would in all certainly been just another statistic. Initial reports showed that there was no trauma to him. His death would have been

If this scene had not been clearly recorded by cell phone, George Floyd would in all certainly been just another statistic. Initial reports showed that there was no trauma to him. His death would have been  through their police departments, while pedophile priests hide behind their clerical garments and the authority of their church.

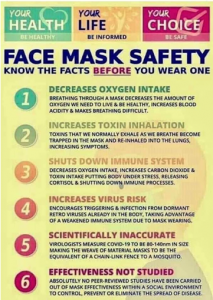

through their police departments, while pedophile priests hide behind their clerical garments and the authority of their church. conjured up dangers of coronavirus. In March 2020, within a month, I watched my country go from an economically rolling, healthy, peaceful, vibrant nation, to a toilet paper hoarding, germaphobe (virus-a-phobe), cowardly nation, afraid of an “invisible enemy” COVID-19, which the perpetually lying mainstream media and the CDC told us we needed to fear. Like children being instructed by our mommies, we were told to wash our hands for 20 seconds, to social distance at least 6 feet apart from each other, to wear masks, and to stay indoors. The sheople of America immediately complied. We were told we needed to quarantine the healthy for 30 days.

conjured up dangers of coronavirus. In March 2020, within a month, I watched my country go from an economically rolling, healthy, peaceful, vibrant nation, to a toilet paper hoarding, germaphobe (virus-a-phobe), cowardly nation, afraid of an “invisible enemy” COVID-19, which the perpetually lying mainstream media and the CDC told us we needed to fear. Like children being instructed by our mommies, we were told to wash our hands for 20 seconds, to social distance at least 6 feet apart from each other, to wear masks, and to stay indoors. The sheople of America immediately complied. We were told we needed to quarantine the healthy for 30 days. The time did come when many Americans had enough, and they declared that they would “peaceably” protest against the unconstitutional COVID-19 edicts being made by various governors throughout the land. But the Democrat governors of these states, such as Governor Whitmer of Michigan, stated that she did not care about the protesters and

The time did come when many Americans had enough, and they declared that they would “peaceably” protest against the unconstitutional COVID-19 edicts being made by various governors throughout the land. But the Democrat governors of these states, such as Governor Whitmer of Michigan, stated that she did not care about the protesters and  However, Americans have sat idly by as we were told by the “experts” at the CDC that they were going to

However, Americans have sat idly by as we were told by the “experts” at the CDC that they were going to  Dennis Kelly

Dennis Kelly not alive. It does not behave as a flea and leap onto unsuspecting victims to infect them. The six foot distance is completely arbitrary as well as fictitious. A more appropriate guideline might be no French kissing while standing in line.

not alive. It does not behave as a flea and leap onto unsuspecting victims to infect them. The six foot distance is completely arbitrary as well as fictitious. A more appropriate guideline might be no French kissing while standing in line. and defy Trump

and defy Trump Corporations and politicians are all on their knees begging for forgiveness. Racism is their fault. It’s absolutely nauseating.

Corporations and politicians are all on their knees begging for forgiveness. Racism is their fault. It’s absolutely nauseating. Perhaps most appalling was watching members of the National Guard ‘take a knee’ in Hollywood, California.

Perhaps most appalling was watching members of the National Guard ‘take a knee’ in Hollywood, California. advocates for the violent overthrow of the government and for the murder of the rich and claims to have international involvement in left-wing movements. The

advocates for the violent overthrow of the government and for the murder of the rich and claims to have international involvement in left-wing movements. The  one of our most basic rights. America is built on protests and peaceful protests are during daylight hours, evil hides in darkness. The lockdown protests were always during the day. Antifa operates at night.

one of our most basic rights. America is built on protests and peaceful protests are during daylight hours, evil hides in darkness. The lockdown protests were always during the day. Antifa operates at night. When President Trump said he wanted to call out the National Guard, he was right, and

When President Trump said he wanted to call out the National Guard, he was right, and  Can you imagine armed troops blocking you from going to school? That’s what happened in

Can you imagine armed troops blocking you from going to school? That’s what happened in  American students were enrolled without further violent disturbances. The law had been upheld, but Eisenhower was criticized both by those who felt he had not done enough to ensure civil rights for African Americans and those who believed he had gone too far in asserting federal power over the states.

American students were enrolled without further violent disturbances. The law had been upheld, but Eisenhower was criticized both by those who felt he had not done enough to ensure civil rights for African Americans and those who believed he had gone too far in asserting federal power over the states. Conclusion

Conclusion As the Coronavirus covered the earth, the Communists began issuing orders to the world in the form of, “medical orders” that told all people that they must be quarantined, wear masks, close all businesses( so as not to spread the virus), and dictate when one can reopen their businesses and where they can go. People cannot gather together. They must stay six feet away from each other. The Communist Party was and is now giving all orders of movement to The United States of America. That was always their desire which they now have accomplished.

As the Coronavirus covered the earth, the Communists began issuing orders to the world in the form of, “medical orders” that told all people that they must be quarantined, wear masks, close all businesses( so as not to spread the virus), and dictate when one can reopen their businesses and where they can go. People cannot gather together. They must stay six feet away from each other. The Communist Party was and is now giving all orders of movement to The United States of America. That was always their desire which they now have accomplished. Actually this was all on board before the 1960’s as all planning and preparing took place behind closed doors that were behind the Iron Curtain. This writer spent time there and personally heard the plans being made. Communists had virtually taken over the motion picture industry and were able to include subtle hints of the superiority of Communist life in their films.

Actually this was all on board before the 1960’s as all planning and preparing took place behind closed doors that were behind the Iron Curtain. This writer spent time there and personally heard the plans being made. Communists had virtually taken over the motion picture industry and were able to include subtle hints of the superiority of Communist life in their films. partisan that Joe Biden’s cognitive impairment was worsening, Democrat desperation––as evidenced by the irrational behavior and statements of their bought-and-paid-for media whores––escalated precipitously. No one who follows this circus should be surprised at what followed.

partisan that Joe Biden’s cognitive impairment was worsening, Democrat desperation––as evidenced by the irrational behavior and statements of their bought-and-paid-for media whores––escalated precipitously. No one who follows this circus should be surprised at what followed. and Black Lives Matter rampaging through American cities and suburbs, destroying businesses, stealing multi millions of dollars of goods, burning cars, defacing monuments, shooting people, throwing the Molotov cocktails and bricks left for them in strategic spots by their fellow thugs, and generally giving the world an up-close, three-dimensional picture of what clinicians call sociopaths and psychopaths.

and Black Lives Matter rampaging through American cities and suburbs, destroying businesses, stealing multi millions of dollars of goods, burning cars, defacing monuments, shooting people, throwing the Molotov cocktails and bricks left for them in strategic spots by their fellow thugs, and generally giving the world an up-close, three-dimensional picture of what clinicians call sociopaths and psychopaths. America is in a battle for its very survival. Christianity is clearly in the sights of the atheistic Left who have seized control of every institution in America. President Trump was sending a message to the pulpits of America when he took the short stroll to church on Monday. Christian America is burning and he needs the churches’ help in the battle for our nation.

America is in a battle for its very survival. Christianity is clearly in the sights of the atheistic Left who have seized control of every institution in America. President Trump was sending a message to the pulpits of America when he took the short stroll to church on Monday. Christian America is burning and he needs the churches’ help in the battle for our nation. “His Mercy Endureth Forever” is Book No. 12 of my “Bell Mountain” series, and it’s about… well, mercy. The mercy that everybody needs, which God holds out to those who seek Him—and even to those who don’t. Some receive mercy, but others turn away from it.

“His Mercy Endureth Forever” is Book No. 12 of my “Bell Mountain” series, and it’s about… well, mercy. The mercy that everybody needs, which God holds out to those who seek Him—and even to those who don’t. Some receive mercy, but others turn away from it. make people dependent on government in their senior years, in exchange for their votes. Social Security is so ingrained in the culture that any politician who dares to utter the words, “we must reform Social Security” will lose his or her political career almost overnight. Now, everyone you do business with wants your once-private social security number for identification purposes, or to track you if you don’t pay them. How did that happen?

make people dependent on government in their senior years, in exchange for their votes. Social Security is so ingrained in the culture that any politician who dares to utter the words, “we must reform Social Security” will lose his or her political career almost overnight. Now, everyone you do business with wants your once-private social security number for identification purposes, or to track you if you don’t pay them. How did that happen? Where are the indictments of the Deep State Criminals? How long must we wait?

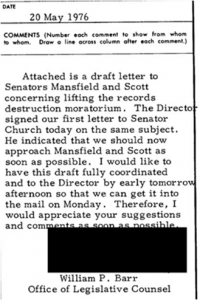

Where are the indictments of the Deep State Criminals? How long must we wait? As President Bush’s most notorious CIA insider from 1973 to 1977, and as the AG from 1991 to 1993, Barr wreaked havoc, flaunted the rule of law, and proved himself to be one of the CIA/Deep State’s greatest and most ruthless champions and protectors.

As President Bush’s most notorious CIA insider from 1973 to 1977, and as the AG from 1991 to 1993, Barr wreaked havoc, flaunted the rule of law, and proved himself to be one of the CIA/Deep State’s greatest and most ruthless champions and protectors. Security Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Internal Revenue Service.Barr stonewalled and destroyed the Committee investigations into CIA abuses.

Security Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Internal Revenue Service.Barr stonewalled and destroyed the Committee investigations into CIA abuses. “Mr. Floyd had underlying health conditions including coronary artery disease and hypertensive heart disease,” said the complaint from the Hennepin County Attorney. “The combined effects of Mr. Floyd being restrained by police, his underlying health conditions and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death.”

“Mr. Floyd had underlying health conditions including coronary artery disease and hypertensive heart disease,” said the complaint from the Hennepin County Attorney. “The combined effects of Mr. Floyd being restrained by police, his underlying health conditions and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death.” struggling to keep the suspect still with the suspect saying, “I didn’t do nothing to you.” The male officer tells the guy to “stop resisting” several times and at one point, he tells the female officer “shoot him!”

struggling to keep the suspect still with the suspect saying, “I didn’t do nothing to you.” The male officer tells the guy to “stop resisting” several times and at one point, he tells the female officer “shoot him!” communities means that officers will be disproportionately confronting armed and often resisting suspects in those communities, raising officers’ own risk of using lethal force,” wrote Heather Mac Donald, a conservative researcher, in a Wall Street Journal column headlined “The Myths of Black Lives Matter”…

communities means that officers will be disproportionately confronting armed and often resisting suspects in those communities, raising officers’ own risk of using lethal force,” wrote Heather Mac Donald, a conservative researcher, in a Wall Street Journal column headlined “The Myths of Black Lives Matter”… DOJ long ago should have put the screws to ANTIFA and declared them a domestic terrorist organization. Perhaps that will happen soon:

DOJ long ago should have put the screws to ANTIFA and declared them a domestic terrorist organization. Perhaps that will happen soon:  Trump insisted on including Jews, blacks at Palm Beach golf course in 1990s

Trump insisted on including Jews, blacks at Palm Beach golf course in 1990s A white woman killed by a Muslim.

A white woman killed by a Muslim.