By Steven Yates

By Steven Yates

February 19, 2024

Probably not, but the narrative wars have likely engendered a period of unrest and decline no matter what happens. There remains hope.

[Author’s note: a somewhat different version of this article is available on my Substack, Navigating the New Normal. The updates are due to this being a developing story.]

Last Thursday (Feb. 8), the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on whether or not Donald Trump should remain on GOP ballots. The allegation, as everybody knows, is that on January 6, 2021, speaking to a throng of supporters from the Ellipse, he fomented an insurrection in the disqualifying sense of the 14th Amendment, Section 3, of the Constitution.

The Court may have decided this case before this has time to go up. I’ve gone ahead with it anyway, because even if (as most of us expect) the Court reverses the Colorado and Maine decisions, we’re nowhere near out of the woods.

While the Supremes seemed more interested in such technical-legalistic matters as whether officer of the United States applies to the presidency, the real question going forward (see here and here) is whether what happened on January 6, 2021 constitutes an insurrection, since Trump told people to march to the Capitol “peacefully and patriotically….” He never suggested anyone go inside the Capitol (it was Ray Epps, possibly among others, who did that!).

This case is unprecedented. We’ve never seen a clash of narratives like this. Those on opposite sides literally do not see the world the same way. They aren’t making the same assumptions about what kind of political system we’re living under. Small wonder some are ready to divide the country — peacefully, if possible; forcibly if necessary. This is where the narrative wars have brought us.

We don’t agree on what really happened that day, six days into 2021. An insurrection, as I explained citing references, is an organized effort to violently overthrow a government. Few who came onto Capitol grounds that day were violent, although there were hotheads on the front lines who broke through barricades, pushed Capitol police to the ground, and broke windows. This was a very small minority of the allegedly 2,000 or so people who entered the Capitol peacefully, some doing no more than walking around for a few minutes and then leaving.

There was no organized effort to overthrow the U.S. government.

So what were they doing? Well over 10,000 people were protesting in Washington, D.C. that day. They had doubts that Joe Biden was elected legitimately. Every effort to pursue the matter through the courts had been rebuffed. Judges did not look at any evidence (e.g., affidavits alleging wrongdoing in Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia). They said either, “there’s no evidence” or they used a legal ploy of “no standing to sue.” The Supreme Court refused to hear appeals.

It became as if the use of phrases like conspiracy theorist and election denialism were sufficient to quell the sense of something amiss.

To this day, tens of millions of Americans think Election 2020 was stolen, even if they don’t agree on the circumstances or how the steal was accomplished.

Their reasoning: a man, arguably showing signs of dementia and staying mostly out of public view, trouncing a man able to fill arenas during a pandemic by 7 million popular votes, makes no sense whatsoever.

They now fear that something similar could happen again, in 2024, and in broad daylight!

The Jan-6ers believed they were trying to save democracy. Today we should fear destruction of real democracy, which reflects the will of the people (even those you disagree with), by those gaslighting us with phrases like saving our democracy!

What will happen this November? I honestly don’t know. But there is no reason to think it’s going to be pretty, with an outcome accepted automatically by both sides.

What then?

Civil War? Or massive civil unrest?

I do not think anything that happens will rise to the level of civil war.

Civil wars happen when discourse over fundamental disputes between two factions, both having sufficient resources to exact their wills on the body politic, breaks down. Laws and policy decisions are then disregarded as both sides battle openly and violently for control over dominant institutions, especially mass media.

Is this what we’re looking at? Not quite.

One problem is with both sides having the resources to exact their wills. I do not think Trump’s side has those resources, no matter how much of his own money Trump still has to spend. With efforts underway to cripple him financially, it’s unclear how much he will have when the dirt settles.

The point of the 91 felony lawfare allegations as well as the civil suits has been to render him impotent, and imprisoned, if that’s what it takes to stop him.

To the extent that groups and organizations backing Trump’s side in the narrative wars have some resources and would be able to mount significant national-scale protests if Trump were refused a spot on national ballots, I am unsure how many have the will.

Look at what’s been done to over a thousand Jan-6ers. Most of these people will never get their lives back. Businesses have been destroyed; homes are gone. Some will be unable to find decent work. They have been demonized in corporate media as “Capitol rioters” and “insurrectionists.” This label may well follow them the rest of their lives.

Is this or is this not a major disincentive to mount mass protests, no matter the provocation?

Moreover, in large crowds many of whose members don’t know all others personally and with no way to vet them, infiltration by the FBI or leftist agent provocateurs is a separate risk. Fear of this happening was probably a factor in undermining the Take Our Border Back Convoy which convened at Eagle Pass, Texas, on Feb. 3: instead of 700,000 attendees, around 7,000 showed up, disappointing those who see securing the border with Mexico as a major issue this year.

A recent discussion with a number of legal scholars, political analysts, and national security experts did not feature a single person who predicts a civil war. Some do, however, predict the sort of scattered disruptions that signify civil unrest. I think we will see unrest whatever the Supreme Court decides, in this or in upcoming cases involving Trump.

What I can’t predict is how much, how long it will last, or what the long term repercussions will be.

Most observers think the Court will set Colorado and Maine aside, ensuring that their ruling applies to all 50 states. According to the 14th Amendment only Congress can invoke the insurrection clause by passing a law, and this isn’t going to happen. This might invite protests from the other side, possibly worse than overturning of Roe v Wade did, because of how the Establishment has presented this situation to the public. Again: “democracy is on the ballot,” Biden has put it. “Democracy itself” is at stake, wax the hysterics (as if the U.S. is really a democracy, which it hasn’t been for a very long time — but never mind that now).

This is how narrative war works.

Assuming Trump is still on ballots as you read this, the globalist-leftist alliance will already be maneuvering full throttle to block a Trump 2.0 administration.

We might see cyberattacks or other false flags to be blamed on Trump supporters. We might even see The Great Taking (see below). Something as sudden as it would be drastic could happen any time between now and November.

I’m not making a prediction here. That would be hazardous. But the fear of Trump 2.0 is palpable.

Bottom line, though: no civil war.

Especially with an Establishment able to command technologies (use of smartphone records, facial recognition, generative AI, etc.) that would make previous tyrants gasp. Plus, I doubt that Homeland Security’s hollow-point bullets have gone anywhere. I’ve seen nothing to suggest that the militarized power centers in the Asylum on the Potomac, if militarized, couldn’t put down any direct domestic challenge to their power with relative ease.

This Is What Civilizational Decline Looks Like.

If we look at the larger sweep of human history, one thing becomes clear: even relatively free societies are very rare. Empires, tyrannies, dictatorships of various sorts, are the norm. In most places and at most times, those in power have done pretty much as they pleased. So is tribalism a norm, almost one of our default settings: “us” versus “them.”

Briefly, Periclean Athens moved towards freedom, but compromised it with slavery, allowed what freedom they had to weaken them in other ways (as Plato observed), the result being the loss of the war with authoritarian Sparta and long-term decline.

The Christian worldview began to create a societal ambience in which there were moral checks on human authority. The powerful couldn’t do as they pleased because they answered to God for their actions. Eventually this ended the idea of “the divine right of kings.” The Christian conviction was that this was a world of physical and moral order. On this foundation rose Western civilization, surely the greatest civilization in human history, via science, technique, property rights, markets, and limits on state power.

By the mid twentieth century we were starting to dismantle the tribal distinctions of the past, via Martin Luther King Jr.’s promotion of judging people “not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Those obsessed with the need to control others, and as much of the world as possible, rebelled against the Christian worldview. They’d removed God from the world picture and had learned to use societal and technological systems others had created against them. The scientific-industrial-educational mainstream became de facto materialist. I say de facto because it is not as if many of their managerial disciples reflected on what they were doing. A few did.

The result has been a slow and painful slide backwards towards what the West had partly escaped: tribalism, naked grabs for power, re-enslavement by economic and technical means, and the obliteration of truth in favor of propaganda, gaslighting, and open and unabashed lying.

The Christian conviction of checks on secular power is gone. The sciences, which honestly sought order and explanation, are now The Science, a form of intellectual authoritarianism funded by corporations and government. Technique no longer solves problems for the whole of the body politic but designs algorithms to bring the masses into passivity and control, incentivizing the masses to ensnare themselves (think: nearly all social media).

Property rights no longer exist as such; all are subject to taxation, and even the conditional ownership implied by deeds-plus-property-taxes is being replaced by rent of various sorts, as home ownership becomes harder and harder to afford.

Markets are not free but controlled, because corporations employ hidden incentives or “nudges” of various sorts; the above-mentioned algorithms Big Tech has perfected “know” more about you than you know about yourself and have honed the science of getting you to consume.

Finally, to speak of morality in the halls of Congress is more likely to prompt gales of laughter than serious reflection on where the country is going.

Legal eagles invoke the Constitution which it serves their agendas, as with those using the 14th Amendment to try to get Trump off ballots. Otherwise, it’s dead.

Is sending money to foreign government fighting wars halfway around the world authorized anywhere in the Constitution? Especially when our own southern border is so porous that thousands of people including possibly dangerous individuals can cross it illegally every month?

Language itself has been perverted. Democracy clearly no longer means government by and for We the People. It is code for one species of elite domination, in which the locus of power isn’t a single figure, such as a Xi or a Putin, but systemic and driven by money. Trump was only able to mount a serious candidacy back in 2015-16 because he could finance his own campaign. Had he lacked those resources, he wouldn’t have registered. Money isn’t everything, of course. It is necessary but not sufficient. If you could literally buy your way into the presidency, Ross Perot and Steve Forbes would have had viable shots back in their day.

Trump had (still has) a great deal of personal charisma, a solid ability to command mass media even if its owners hate his guts, and things to say that resonate with an increasingly disillusioned Republican audience.

He was an existential threat to those who think in terms of global power (globalists) and cultural dismemberment (the brand of hard-leftist that’s obsessed with transgenderism). This is the case even if he has no systematic philosophy of his own. He’s a disruptor by nature. Disruption works, especially when institutions are losing their sense of legitimacy. This loss of legitimacy is characteristic of long-term decline. Many of those behind Trump have no trouble dynamiting (figuratively speaking, of course) something that ceased to work for them long ago.

Trump 2.0 would be an even bigger existential threat to global power and leftist dismemberment because there’s no doubt he’s far more knowledgeable about how to work governing systems now than he was in 2017.

Hence the constant barrage of fear porn from every corporate media outlet, every major magazine, all the dominant political voices in unison.

I’ve no idea how likely a Trump 2.0 administration is. As I’ve said, globalist-leftist power and propaganda will do everything they can to keep it from happening.

What we can be sure of is that should Trump be reelected, it wouldn’t guarantee anything. Anyone who thinks this will quell globalist-financed leftist street protests, probably violent, even if Trump invokes the Insurrection Act, is kidding himself.

The next year, 2025, could turn out to be more volatile and violent than anything 2024 served up.

The next administration will face combined challenges: rising homelessness, the debt explosion, the southern border, fentanyl, continued demands by foreign leaders with an entitlement mindset like Zelenskyy, continuing unrest in the Middle East, the possibility of China encircling Taiwan, and more.

I have no trouble envisioning complete paralysis.

The U.S. rose empowered by the magnificent thoughts of the James Madisons and George Washingtons and Thomas Jeffersons of the day. There are no thinkers of that caliber anywhere to be found in our present-day political or moneyed classes. Nor is the view that directed hard work is what builds and sustains civilizations the prevailing one, and even if it were, today’s institutions are designed to reward political connections and politically correct ideology far more than hard work. The latter is a threat to those who have learned how to exploit and profit from the present system.

This is what civilizational decline looks like.

What Happens Next?

I don’t like making predictions. So, I just draw scenarios, and I’ve never had so many in all my pockets at one time. I’ve even heard serious suggestions that there might not even be an election this November.

What do we see? Two mighty forces on collision course!

Those tendencies conveniently labeled “populism”: ordinary people rising up against powerful elites everywhere: in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., France, The Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Israel, and elsewhere. In a few countries (India, Hungary, Italy), counter-elites have won public office. Counter-elite Jair Bolsonaro was in control in Brazil but tossed by corrupt leftists who are trying to imprison him. A counter-elite named José Antonio Kast, a conservative, could become president of Chile if he decides to run in Chile’s next election (2026). Chile’s presently-dominant leftists are also struggling with inflation and dysfunction.

You know the counter-elites and their supporters because globalist-controlled corporate media demonizes them as extremists, conspiracists, white supremacists, protofascists, spreaders of misinformation, etc., etc.

Globalists (WEF/Davos, the UN/WHO axis, big foundations / funding networks such as Soros’s and Gates’s, others) doubtless fear the unraveling of everything they’ve spent lifetimes working towards. If they lose, they could end up hanging from lampposts! They damned well know it!

It is important not to underestimate what these psychopaths might be capable of! Some do that. (Example here.)

I’m thinking again of The Great Taking. Download the book for free here; David Rogers Webb discusses the book at length here; read my commentary here; lengthy interview with Webb here; another very worthwhile discussion here. We’re hearing warnings of possible cyberattacks, conceivably at the hands of some of those who entered the U.S. illegally which include Chinese nationals as well as Hezbollah sleeper cells awaiting activization on command from the disrupted Middle East.

A single, well-planned and well-placed cyberattack could cripple American infrastructure, take down part or all of the Internet for a time, and bring the global financial system to its knees.

Forget bitcoins and other crypto. Your wallets will be useless pieces of paper.

CBDCs would be introduced as the “fix.” If covid-19 was the biggest power grab we’d ever seen, CBDCs would quickly surpass that.

You’d be allowed back on a vastly more controlled Internet with government-issued ID (e.g., a passport). No more anonymity.

CBDCs (Central Bank Digital Currencies) would then be downloadable via an app in your phone and could be programmed to work only during a specific time duration (to ensure that you consume), to purchase certain goods or services but not others (to ensure that you consume what those in power want you to consume), and to function only within a given radius (in case the programmers have been told by their masters to restrict peasant movement, as in the “sustainable cities” WEF globalists envision).

Cash would, of course, disappear as a casualty of the financial calamity. Cash can’t be tracked or traced or monitored.

Few would be in a position to resist — presumably mass starvation is not an option! Those stuck in big cities would find themselves in a dystopia that would make present-day China look like a paradise by comparison.

Dissent? Your CBDC would be turned off, so that you can’t buy food.

Hope.

There remains hope, of course, and it is important not to lose sight of this.

We also learn from history that events move in long cycles. Civilizations rise, then they decline and fall. Most fall from within. Discussions of how cycles work are readily available (start here). There are conditions on a society’s existence, and if those conditions cease, it finds itself living on borrowed time.

Economies based exclusively on debt eventually collapse. The track record is 100 percent.

“Prophets” try to point this out and draw attention to the problems. Initially they are dismissed as “doomers-gloomers” and denounced in controlled media. The masses are either too insouciant to listen or just too busy trying to survive.

But “prophets” always find a following that has figured out the truth. Some refer to this following as a remnant (Isaiah 1:9). This remnant will build up a new society, restoring values and practices that work.

We are clearly in a decline phase. Our “prophets” are increasingly listened to. There are remnant communities already out there, organizing a “parallel economy” mostly outside the grid. Others are in the planning stages.

Such groups, like the Amish, would be far less affected by a Great Taking.

The future, I submit, lies with those who can take charge of their own educations and lives, learn to sustain themselves growing their own food so that they don’t need CBDCs or even cash for purchases, developing barter systems where necessary.

They will be closer to the natural order and therefore closer to God, the Creator and Author of nature and therefore of real sustainability before globalists hijacked that term and used it for their own insidious purposes.

One thing is for sure: building communities outside the power systems and sustaining them while riding out whatever occurs will take resilience. How many of us are working on that?

© 2023 Steven Yates – All Rights Reserved

E-Mail Steven Yates: freeyourmindinsc@yahoo.com

____________________

I have it on excellent authority that in the wake of the counterattacks against alternative (i.e., truthful) media, this site is struggling to survive. Please consider making a donation to support NewsWithViews.com here.

Steven Yates has a Patreon.com page. Donate here and become a Patron if you benefit from his work and believe it merits being sustained financially.

Steven Yates’s book Four Cardinal Errors: Reasons for the Decline of the American Republic (2011) can be ordered here.

His philosophical work What Should Philosophy Do? A Theory (2021) can be obtained here or here.

His paranormal horror novel The Shadow Over Sarnath (2023) can be gotten here.

Should you purchase any (or all) books from Amazon, please consider leaving a five-star review (if you think they merit such).

By Karen Schoen

By Karen Schoen By Frosty Wooldridge

By Frosty Wooldridge By Coach Dave Daubenmire

By Coach Dave Daubenmire Last week tornadoes ravage Western Ohio. Indian Lake is a name that may be familiar to some of the old folks because it was the name of a Song made famous by the singing family THE COWSILL’s. Do you remember the lyrics “Indian Lake is a scene you should make with your little ones. Just keep it in mind if you’re looking to find a place in the Summer sun. Swim in the cove, have a snack in the grove or you can rent a canoe. At Indian Lake you’ll be able to make the way the Indians do.”

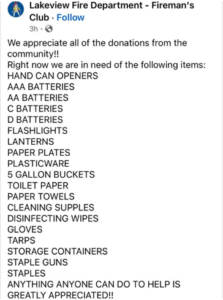

Last week tornadoes ravage Western Ohio. Indian Lake is a name that may be familiar to some of the old folks because it was the name of a Song made famous by the singing family THE COWSILL’s. Do you remember the lyrics “Indian Lake is a scene you should make with your little ones. Just keep it in mind if you’re looking to find a place in the Summer sun. Swim in the cove, have a snack in the grove or you can rent a canoe. At Indian Lake you’ll be able to make the way the Indians do.”  Could you help us help the folks in Indian Lake? Many have lost everything. At least three people died. Please watch

Could you help us help the folks in Indian Lake? Many have lost everything. At least three people died. Please watch  The list seems so simple…and desperate.

The list seems so simple…and desperate. by Lee Duigon

by Lee Duigon By Steven Yates

By Steven Yates By Bradlee Dean

By Bradlee Dean By Kelleigh Nelson

By Kelleigh Nelson By: Amil Imani

By: Amil Imani By Paul Engel

By Paul Engel By: Devvy

By: Devvy By Sidney Secular

By Sidney Secular by Rolaant McKenzie

by Rolaant McKenzie

By Pastor Mike Spaulding

By Pastor Mike Spaulding By Rob Pue

By Rob Pue By Reverend Glynn Adams

By Reverend Glynn Adams By Lex Greene

By Lex Greene By Ms. Smallback

By Ms. Smallback Seventeen people died in the path of that tornado in Topeka, and another 550 were injured, not to mention the costliest damages to date in its history. The tornado took 26 minutes to pass through the city. I wonder what the numbers would have been if the whole city had heeded the warning?

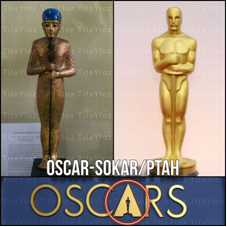

Seventeen people died in the path of that tornado in Topeka, and another 550 were injured, not to mention the costliest damages to date in its history. The tornado took 26 minutes to pass through the city. I wonder what the numbers would have been if the whole city had heeded the warning? The intersection of the two eclipses being at Little Egypt says a lot by itself. Egypt, of course, is representative of idolatry – of which America has become a land full of. More telling than that is the particular “gods” mainstream America has adopted.

The intersection of the two eclipses being at Little Egypt says a lot by itself. Egypt, of course, is representative of idolatry – of which America has become a land full of. More telling than that is the particular “gods” mainstream America has adopted. Eye witness accounts of invading mercenaries through our defenseless border describe terrorists on the FBI terrorist lists, murderers, rapists, traffickers, Chinese secret police, Middle Eastern terrorists who had the boldness to tell the video journalist, “You don’t know who I am? You will.”… Countless more have been videoed coming across with full military style weaponry and body armor. And the one that makes my blood boil, people they say who have been sent by the U.N. These people have been given money and addresses to head to. This aren’t the huddled, tired masses. This is an invasion of mercenaries with marching orders waiting for the “go” signal.

Eye witness accounts of invading mercenaries through our defenseless border describe terrorists on the FBI terrorist lists, murderers, rapists, traffickers, Chinese secret police, Middle Eastern terrorists who had the boldness to tell the video journalist, “You don’t know who I am? You will.”… Countless more have been videoed coming across with full military style weaponry and body armor. And the one that makes my blood boil, people they say who have been sent by the U.N. These people have been given money and addresses to head to. This aren’t the huddled, tired masses. This is an invasion of mercenaries with marching orders waiting for the “go” signal. John Cornyn’s

John Cornyn’s  By Cliff Kincaid

By Cliff Kincaid By Coach Dave Daubenmire

By Coach Dave Daubenmire By Oregon State Senator, Dennis Linthicum

By Oregon State Senator, Dennis Linthicum by Tom DeWeese

by Tom DeWeese by Peter Falkenberg Brown

by Peter Falkenberg Brown By George Lujack

By George Lujack By Coach Dave Daubenmire

By Coach Dave Daubenmire By Dennis Kelly

By Dennis Kelly prostitute media might call them racists. Republicans who don’t want to offend voters in their district while our country is being invaded and believe me, the crime wave is increasing by the day.

prostitute media might call them racists. Republicans who don’t want to offend voters in their district while our country is being invaded and believe me, the crime wave is increasing by the day. A warrior or a senator like Susan Collins, R-Maine? Pro-killing the unborn, voted yes to add sexual deviants to the list of hate crimes for which Congress has NO legislative authority, free-trade advocate to keep destroying our most important job sectors; that’s a very short list. Why she hasn’t registered with the Democrat/Communist Party USA is a mystery.

A warrior or a senator like Susan Collins, R-Maine? Pro-killing the unborn, voted yes to add sexual deviants to the list of hate crimes for which Congress has NO legislative authority, free-trade advocate to keep destroying our most important job sectors; that’s a very short list. Why she hasn’t registered with the Democrat/Communist Party USA is a mystery. Scalise (R-LA), Elise Stefanik (R-NY) and Tom Emmer (R-MN) are seated next to Speaker Johnson. Scalise votes with the Constitution 67% of the time, Stefanik 60% and Emmer 70%.

Scalise (R-LA), Elise Stefanik (R-NY) and Tom Emmer (R-MN) are seated next to Speaker Johnson. Scalise votes with the Constitution 67% of the time, Stefanik 60% and Emmer 70%. Is he naive or one of them? The Stalinist Democrat Party is who put J6ers in prison. It is why Speaker Johnson courageously blurred the faces of people at the Capitol on January 6th on the portions of the videos released.

Is he naive or one of them? The Stalinist Democrat Party is who put J6ers in prison. It is why Speaker Johnson courageously blurred the faces of people at the Capitol on January 6th on the portions of the videos released. By Edwin Vieira, JD

By Edwin Vieira, JD Free will is the defiant flicker of individuality against the relentless backdrop of determinism. The sculptor carves purpose from the raw marble of circumstance, weaving a unique narrative from the threads of experience. It is the alchemist, transforming the base metals of circumstance into the gleaming gold of personal destiny. Free Will is the beacon of light that illuminates the path of our existence. It is the essence of our sovereignty as sentient beings, empowering us to navigate the labyrinth of life with courage, conviction, and unwavering resolve.

Free will is the defiant flicker of individuality against the relentless backdrop of determinism. The sculptor carves purpose from the raw marble of circumstance, weaving a unique narrative from the threads of experience. It is the alchemist, transforming the base metals of circumstance into the gleaming gold of personal destiny. Free Will is the beacon of light that illuminates the path of our existence. It is the essence of our sovereignty as sentient beings, empowering us to navigate the labyrinth of life with courage, conviction, and unwavering resolve. by Kathleen Marquardt

by Kathleen Marquardt By Kat Stansell

By Kat Stansell

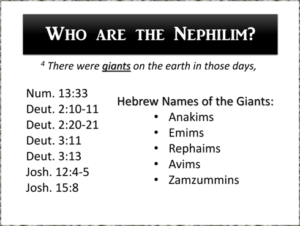

Both Daniel and Enoch call these beings “Watchers”, which is ’iyr in the Aramaic that literally means watcher, but the translators have implied as angels or guardians. It comes from the root word ‘uwr meaning “through the idea of opening the eyes”, from the root “to be bare”. Best hypothesis is these are created beings with the task of watching creation. They’re listed three times in Daniel in chapter four and each time they are coupled with the “holy ones” (which is also an Aramaic word) which loosely translates one made sacred. Each time in Daniel they’re used is to issue a decree.

Both Daniel and Enoch call these beings “Watchers”, which is ’iyr in the Aramaic that literally means watcher, but the translators have implied as angels or guardians. It comes from the root word ‘uwr meaning “through the idea of opening the eyes”, from the root “to be bare”. Best hypothesis is these are created beings with the task of watching creation. They’re listed three times in Daniel in chapter four and each time they are coupled with the “holy ones” (which is also an Aramaic word) which loosely translates one made sacred. Each time in Daniel they’re used is to issue a decree. • Paramount’s logo is a towering mountain with 22 stars encircling its top which is strangely parallel to Mount Hermon, (the mount the ancient gods left their abode in Heaven to fornicate on earth). The 22 stars are strangely parallel to the 22 named gods or beings that led the 200 in the rebellion of their original corruption of earth.

• Paramount’s logo is a towering mountain with 22 stars encircling its top which is strangely parallel to Mount Hermon, (the mount the ancient gods left their abode in Heaven to fornicate on earth). The 22 stars are strangely parallel to the 22 named gods or beings that led the 200 in the rebellion of their original corruption of earth. The entertainment industry is ripe with god worship. In fact, watching a music video these days is like having a front seat to an occult ritual. Pretty much anything by Beyonce, Lady Gaga, JayZ, Marilyn Manson, Katy Perry, Madonna, Taylor Swift, and the list goes on and on….is witnessing some form of homage to their god(s) and/or some ritual.

The entertainment industry is ripe with god worship. In fact, watching a music video these days is like having a front seat to an occult ritual. Pretty much anything by Beyonce, Lady Gaga, JayZ, Marilyn Manson, Katy Perry, Madonna, Taylor Swift, and the list goes on and on….is witnessing some form of homage to their god(s) and/or some ritual. The days of the week, the months of the year – almost all are named after gods. Many holidays are rooted in ancient god worship celebrations.

The days of the week, the months of the year – almost all are named after gods. Many holidays are rooted in ancient god worship celebrations. I could go on and on about the various god/idol symbolism imagery that permeates our culture. I have files and files of images and history. But the point is, the people entrenched in service and worship of their gods (little g) pay homage to their gods in their various venues. Just like a Christian displays a fish, a cross, three crosses, various aspects of God in their lives both personal and public (think personalized license plates, bumper stickers, t-shirts, business logos, sports teams, scripture references, names of the real God, etc.), so do the adherents to foreign gods display their loyalty and adoration for their gods.

I could go on and on about the various god/idol symbolism imagery that permeates our culture. I have files and files of images and history. But the point is, the people entrenched in service and worship of their gods (little g) pay homage to their gods in their various venues. Just like a Christian displays a fish, a cross, three crosses, various aspects of God in their lives both personal and public (think personalized license plates, bumper stickers, t-shirts, business logos, sports teams, scripture references, names of the real God, etc.), so do the adherents to foreign gods display their loyalty and adoration for their gods. By Attorney Rees Lloyd

By Attorney Rees Lloyd by Idaho State Senator Phil Hart

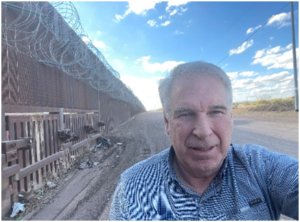

by Idaho State Senator Phil Hart (Pictured here is Cochise County Arizona Sheriff Mark Dannels, center, with Senator Phil Hart, right, and Johnothan Alexander on the left of Live Border News, November 27, 2023, Sierra Vista Arizona. Cochise County and Santa Cruz County to its west see 25% of the fentanyl coming across it’s border with Mexico.)

(Pictured here is Cochise County Arizona Sheriff Mark Dannels, center, with Senator Phil Hart, right, and Johnothan Alexander on the left of Live Border News, November 27, 2023, Sierra Vista Arizona. Cochise County and Santa Cruz County to its west see 25% of the fentanyl coming across it’s border with Mexico.) Sen. Hart in Douglas Arizona (Cochise County) at the Mexico border November 26, 2023

Sen. Hart in Douglas Arizona (Cochise County) at the Mexico border November 26, 2023 by Lynne M Taylor

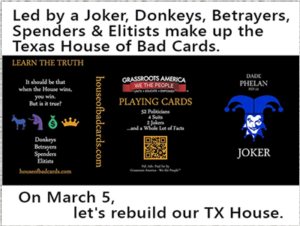

by Lynne M Taylor Right now they’re warning Texans: WARNING! “There is an active effort among ANTI-CONSERVATIVE groups (from the Left and the Right) to mobilize Democrats to vote in the Republican Primary! Their only mission is to defeat conservative candidates. For the March 5 Primary, we MUST turn out record numbers of Republicans who normally wait to vote in November against Democrats.

Right now they’re warning Texans: WARNING! “There is an active effort among ANTI-CONSERVATIVE groups (from the Left and the Right) to mobilize Democrats to vote in the Republican Primary! Their only mission is to defeat conservative candidates. For the March 5 Primary, we MUST turn out record numbers of Republicans who normally wait to vote in November against Democrats.  Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe Knowing that federal political campaign advertisements could not be censored, Bukovinac decided to run for president as a Democrat in 2024 to expose the reality of abortion, show its victims, and give them a voice. Her commercials showed graphic images of aborted babies with the purpose of moving the American people to end this evil practice.

Knowing that federal political campaign advertisements could not be censored, Bukovinac decided to run for president as a Democrat in 2024 to expose the reality of abortion, show its victims, and give them a voice. Her commercials showed graphic images of aborted babies with the purpose of moving the American people to end this evil practice. The Nephilim

The Nephilim By Cherie Zaslawsky

By Cherie Zaslawsky

By Kelleigh Nelson

By Kelleigh Nelson Meckler’s Article V convention will not be limited as he claims. Globalist Council on Foreign Relations member, Robert George sits on the board of CoS. He has already

Meckler’s Article V convention will not be limited as he claims. Globalist Council on Foreign Relations member, Robert George sits on the board of CoS. He has already  Having purchased California avocadoes with this coating, once they felt soft enough to be ripe, when you cut into them, the center is still hard, but the fruit inside the peel is mushy and often rotten.

Having purchased California avocadoes with this coating, once they felt soft enough to be ripe, when you cut into them, the center is still hard, but the fruit inside the peel is mushy and often rotten. “Federal” Reserve is part of our government. After all, it’s called the Federal Reserve! How wrong I was. Dozens of books later, thousands of hours of reading them, Dr. Vieira’s two volume tome, Pieces of Eight, as well as so many of his speeches, I learned the truth about the central bank. It IS the head of the beast dragging us over the abyss. A ravenous beast devouring everything in its path, sucking the life blood of this country for 100 years come Dec. 23, 2013.

“Federal” Reserve is part of our government. After all, it’s called the Federal Reserve! How wrong I was. Dozens of books later, thousands of hours of reading them, Dr. Vieira’s two volume tome, Pieces of Eight, as well as so many of his speeches, I learned the truth about the central bank. It IS the head of the beast dragging us over the abyss. A ravenous beast devouring everything in its path, sucking the life blood of this country for 100 years come Dec. 23, 2013. are just renames of older gods. The famous ten plagues of Exodus were specific plagues to reveal to the world (Egypt was the world power at the time) the inability of the pantheon of gods to thwart the Supreme God. God took on the gods of the most powerful nation at the time, and removed His people from their midst by defeating the Egyptian gods.

are just renames of older gods. The famous ten plagues of Exodus were specific plagues to reveal to the world (Egypt was the world power at the time) the inability of the pantheon of gods to thwart the Supreme God. God took on the gods of the most powerful nation at the time, and removed His people from their midst by defeating the Egyptian gods. “Tell you what. Dump the puppies and buy me lunch, and I’ll give you a fascinating report from home. I know you haven’t been to Iran for a while, and I just returned yesterday. I’ll give you an exclusive so you can write about it and keep raking it in.”

“Tell you what. Dump the puppies and buy me lunch, and I’ll give you a fascinating report from home. I know you haven’t been to Iran for a while, and I just returned yesterday. I’ll give you an exclusive so you can write about it and keep raking it in.”