By Dr. Dennis Cuddy, Ph.D.

By Dr. Dennis Cuddy, Ph.D.

October 18, 2022

This October 16 marks the beginning of the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. What follows is my longer than usual research article about what actually happened during that crisis, which has been portrayed for the last 60 years as President Kennedy’s triumph over the Soviets. Actually, the Soviets won the confrontation.

With the recent television documentary, “Nuclear Nightmare: Inside the Cuban Missile Crisis,” there is renewed interest in Graham Allison’s path-breaking book, ESSENCE OF DECISION. In his book, Allison asked the basic questions: Why did the Soviet Union decide to place offensive missiles in Cuba? And why and how did the United States react the way it did by establishing a quarantine around that island nation?

At the conclusion of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis between the United States and the Soviet Union, the withdrawal by the U.S.S.R. of offensive missiles from Cuba was heralded as a great victory for President Kennedy. But in exchange for this withdrawal, the president guaranteed the safety of Castro’s Cuba from additional invasion attempts from the United States. What a few of us have asked since that time was, what if the guarantee was what the Soviets expected all along?

In late January [1989], top-level Soviet, American and Cuban officials who had been involved in the missile crisis held a two-day conference in Moscow in which Sergei Khrushchev, son of the late Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, admitted, “Even in event of an American invasion of air strike, Soviet officials in Cuba had no orders to use the missiles.”

That only stands to reason, because what sense would it have made for the U.S.S.R. to risk nuclear confrontation with the United States just to obtain offensive missiles in Cuba, 90 miles from the American mainland, when nuclear-armed Soviet submarines could come even closer to our Eastern, Southern and Western coasts? Would it not have made more sense for the Soviet Presidium to conclude that because the United States was militarily superior, there was no way to win a nuclear fight?

However, since American missiles were still in Turkey (despite earlier orders by the president to remove them), this gave the Soviets an excuse to place missiles in Cuba. Of course, this would be followed by an American objection to their presence, and the U.S.S. R. could then appear conciliatory by offering to remove the missiles in exchange for the removal of ours from Turkey along with a guarantee for the safety of Castro’s Cuba from American intervention.

But what evidence is there that the Soviets expected an eventual withdrawal of missiles from Cuba in exchange for the safety guarantee? This evidence is as follows:

- In his [book] Graham Allison stated: “Missile deployment and evidence of Soviet actions toward détente poses an apparent contradiction.”

- The Soviets knew of Cuban U-2 flights.

- The missiles were left uncamouflaged.

- The Soviets did not coordinate installation of the medium-range ballistic missiles with the completion of the surface-to-air missile covers.

- The Soviet Union had never before placed missiles in any nation beyond its borders, not even in its satellites in East Europe.

- Cuba hypothetically could eventually expel the Soviet technicians (as Anwar Sadat later did in Egypt) and do whatever it pleased with the missiles – perhaps take actions that would result in World War III (a situation not to be encouraged by the U.S.S.R.) or perhaps allow American acquisition of the missiles if friendly relations were re-established between Cuba and the United States.

- The United States had already attempted one invasion and would certainly succeed with a second one if it so chose.

- The Soviets desired to avert a nuclear confrontation, yet wanted to use Cuba as a training ground for Latin American revolutionaries.

- And perhaps the best argument for this hypothesis is the post fact one of recent history – the missiles were removed in exchange for the safety guarantee, and Cuba has been used for the training of revolutionaries.

In contrast to the frame of analysis used by Stanley Hoffman at the time, Allison assumed that “governmental behavior can be most satisfactorily understood by analogy with the purposive acts of individuals,” and attempted to answer the aforementioned questions by utilizing three models of analysis: (1) along one dimension they represent different levels of aggregation: nations or national governments, organizations, and individuals; (2) along a second dimension, they represent different patterns of activity: purposive action toward strategic objectives, routine behavior toward different organizational goals, and political activity toward competing goals. However, he admitted that “the three models of the determinants of governmental action do not exhaust the dimensions on which they are arranged.”

The author also admitted at the beginning of his book that he was confused about where the models begin and end (“which is the head and which is the tail of my own dog”). In answer to the question of distinction regarding the beginning and end of the respective models, it is the opinion of this writer that there is no distinction, that all three models should be combined with the organizational model serving as the foundation for the bureaucratic perspective, which in turn is the foundation for the rational model – each perspective moving from lesser decision-making points, and from a large number of actors to an ever smaller number with the realization that the actors are conditioned by their perception of national ideology, personal, and political motives. Therefore, in the summary and analysis of this work, each model will be described in that order (MII: the Organizational Mode, MIII: the Bureaucratic Model, and MI: The Rational or Classical Model).

With regard to MII, Allison maintained that the primary questions are of what organizations and organizational components does the government exist; which organizations traditionally act on which problems; how do they make information available, generate alternatives to solutions about problems, and implement alternative courses of action? To support this model, he maintained that government consists of a conglomerate of semi-feudal, loosely allied organization, …and perceives problems through organizational sensors (even their perception of the national interest is shaped by their organizational self-interests)… acting as these organizations enact routines (SOPs: Standard Operating Procedures).

Still, it seems to this writer that a decision has to be reached, especially in crises, and it is difficult to believe that the decision the United States made to respond to the Soviet action in a particular manner can be best explained in terms of the views and actions of several organizations. Rather it would seem that the goals, weighing of alternatives, and political and ideological concerns of a president, group of men, or a “victorious group” over opposing groups would be a more viable explanation. Other, more specific, reasons exist for questioning MII:

- Allison did not distinguish between “a unified group of leaders” in MII and “leadership clique” in MI.

- The author used Herbert Simon’s “bounded rationality” (a reaction to “comprehensive rationality”) regarding “uncertainty avoidance” which states “people in organizations are quite reluctant to base actions on estimates of an uncertain future.” Yet, people might find themselves compelled to do just that in a crisis situation such as the CMC.

- Allison also referred to Cyert and March of the Carnegie school who emphasize organizational decision “as choice made in terms of goals, on the basis of expectations.” But as with Simon, they have the same problem with their reasoning concerning “uncertainty avoidance.”

- He utilized business organization theory to a slight degree, but that theory incorrectly assumes a perfectly competitive environment.

- SOPs explain how something might have had to occur if it did actually occur, but this is nothing more than saying for a human being to perform some physical exercise, it is necessary to move some part of the body. SOP’s do not explain the all-important “why” when decisions are made.

- MII lacks an explanation of the actual crisis moves, made by each side in response to the opposition’s actions, and the attendant results.

- The author made far-reaching assumptions about Soviet motives with little evidence at all to support them.

- To make assertions such as “an organization in the United States intelligence made an incorrect prediction that the Soviets would not introduce offensive missiles into Cuba” in no way answers the questions, “Why did the Soviets choose to place the missiles there?” and “How did the United States make the decision it did to quarantine Cuba?”

- In this section Allison actually made statements that seem to support MI:

- a) “The Soviet decision to place missiles in Cuba must have been taken within a very narrow circle and implemented with utmost secrecy.”

b)“The final decision to put missiles in Cuba must have been made in the Presidium.”

Of course, organizations have influence, their own unique perspectives, control of certain information, and effect the decision-making process; but to explain the CMC in those terms alone seems no more useful than to explain it in terms of either MIII or MI alone.

Concerning MIII, Allison stated that the essential questions are: what are the existing action channels for producing actions; which players are involved; what pressures and deadlines are there; and what foul-ups are likely? In support of this model, he asserted:“

- leaders who sit on top of organizations are not a monolithic group.”

- A Presidential or high directive does not necessarily guarantee action by the bureaucracy.

- “government action is a political resultant. What happens is not chosen as a solution to a problem but rather results from compromise, conflict, and confusion of officials with diverse interests and unequal influence.

- Positions define what players both might and must do.

- ‘solutions’ to strategic problems are not discovered by detached analysts focusing coolly on the Each player focuses not on the total strategic problem but rather on the decision that must be made today or tomorrow.

- Most problems are framed, alternatives specified, and proposals pushed by ‘Indians,’ (as opposed to ‘Chiefs’).

Yet there seem to be several flaws in the MIII perspective:

- Under the section, “Goals and Interests,” there is no mention of possible political goals and interests.

- The implication that the CMC was a resultant of bargaining within each government’s bureaucracy is difficult to imagine.

- In this section the author emphasizes personal characteristics and opinions in Ex Com, which supports MI – the “victorious actors” over the other actors – rather than the MIII.

- Also, emphasis is placed on the intense interaction between Kennedy and Khrushchev, with the implication that the fate of the world was in the hands of two individuals (MI – “first… both the President and the Chairman bypassed the formal machinery in favor of ad hoc groups”).

- In the section on “the Deal,” Allison speaks of presidential conversations, the President acting against advice, and presidential decisions (MI).

Naturally, just as with organizations, bureaucracies have influence, their own unique perspectives, control of certain information, and effect the decision-making process; but again, to explain the CMC in these terms alone seems no more useful than to explain it in terms of either MII or MI alone.

Regarding MI, Allison stated that the main questions are what is the problem; and what are the alternatives, strategic costs and benefits, pattern of national values, and external or international pressures? MI is a value-maximizing model in which behavior reflects purpose or intention and action is chosen as a calculated solution to a strategic problem. Values and goals are defined and ranked by priority, and then one chooses among several alternatives how to achieve a particular goal by considering the risks and costs of choosing each alternative. Contrary to what one might expect, MI is not as limited as Hans Morgenthau’s attempt to explain national action by reference to a single goal, but it rather follows Raymond Aron’s explanation that “governments pursue a spectrum of goals.”

Allison was quite correct in asserting that “the ‘maker’ of government policy is not one, unitary, rational, centrally controlled, completely informed, value-maximizing, calculating decisionmaker.” But no one seriously believes that anyone is “completely informed’ anyway. He was on more solid ground with his criticism of the inelastic, explicit “rigorous model of action” in MI, for often the decision-making process is elastic and implicit.

This writer will not waste the reader’s time by summarizing each hypothesis for the placement of missiles in Cuba given by the author under MI but will only offer an additional hypothesis and judge which of Allison’s hypotheses seems most convincing. As stated earlier, it is the hypothesis of this writer that the Soviet Union actually wanted the missiles discovered during construction in order to bargain for a guarantee for the safety of Castro’s Cuba from an attack from, by, sponsored by, or funded in any way by the United States.

It seems that one must distinguish in the matter of the CMC between what the Soviet Union might have “hoped for” and what they “wanted or expected.” They might have hoped for all they could get (e.g., offensive missiles in Cuba). On the other hand, it is possible that they psychologically pushed the stakes up in order to obtain their “fall back” objective of the guarantee. President Kennedy had not performed well at Vienna and may have backed down – if that were the case, so much the better for Khrushchev. If the President became tough though, the Soviets did not want a third World War. Allison remarks that commentators speculated that the Soviets wanted the missiles discovered during construction, but he says, “a Soviet desire to be found out hardly squares with the clandestine fashion in which the missiles were transported to Cuba and from the docks to the sites.” On the contrary, it squares exactly – what good would it have done for the Soviets to “announce,” for all intents and purposes, that they were going to send missiles to Cuba or at the dock there? What concessions could have been gained? The United States could have more effectively quarantined Cuba or made surgical air strikes more confidently, among other alternatives. With the missiles already in Cuba and at their sites, on the other hand, a quarantine would not have removed the missiles there and even surgical air strikes would have hit civilians and placed the United States in an unfavorable light in world affairs, especially in Latin America.

If one does not find this writer’s additional hypothesis tenable yet accepts the distinction between what the Soviet Union “hoped for” and what they “wanted or expected,” then it seems that Allison’s fourth hypothesis is most believable. Though in retrospect most people find Hypothesis Five the most obvious, the fourth hypothesis serves as a better venue for supporting the use of MI over MII or MIII:

- The CMC set the climate of opinion in which the United States government would react to hostilities in Vietnam, Latin America, and elsewhere during the 1960’s.

- This hypothesis would explain better than MII or MIII foul-ups why the Soviet Union proceeded with the installation of the missiles even though President Kennedy had spoken in terms that Chairman Khrushchev could not misunderstand about “the grace consequences that such an action would set in motion.”

- Most importantly, according to Theodore Sorensen, President Kennedy himself explained the Soviet action in terms of Hypothesis Four.

Still, why did the Soviet Union seemingly push the situation to the brink of nuclear war? Allison commented that “perhaps some deal” was made. Though not proposing that there is conclusive proof of anything conspiratorial in this regard, a “deal” would help to explain many of the author’s unanswered questions. Possible indications that such a deal might have been made are as follows:

- After the Bay of Pigs and Vienna, President Kennedy needed something by which he could regain prestige.

- Chairman Khrushchev took the U-2 flight over the Chukotka Peninsula “extremely” well considering the existing tense situation; and President Kennedy’s response to news of the errant flight was an “ironic laugh,” and his statement, “There is always some son-of-a-bitch who doesn’t get the word.”

With regard to Allison’s assertion that the response of the United States to place a quarantine around Cuba was a good “middle course” of action, he felt that decision placed the burden of response on Khrushchev. However, one might offer the exact opposite interpretation that the American action took the final decision out of President Kennedy’s hands, and the reader will remember the result of a similar action taken by President Woodrow Wilson concerning the German’s use of submarines in World War I. The author further contended that a naval confrontation in the Caribbean would be perhaps the best type of engagement possible if one had to occur, but one might ask what if the Soviet Union was willing to lose a few ships and missiles in Cuba to have a pretext for striking Berlin or American missiles in Turkey? Even if one were to accept the argument that what President Kennedy did would, in fact, make Khrushchev back down, what would have been the harm in issuing publicly both an ultimatum – “get the missiles out of they will be blown out” – and a concession – “our missiles will be withdrawn from Turkey” (which President Kennedy had already ordered done anyway)? Some maintain that the President could not afford to show weakness after Vienna, but would not the United Nations have seen and world opinion supported Chairman Khrushchev as having the more valid argument that if missiles were in Turkey, why not in Cuba? At any rate, the entire matter does not seem to have been handled in the most “rational” manner; yet perhaps much of the difficulty in accepting MI lies within the meaning of the term “rational” itself. Even though there may be several alternative solutions to one problem, there is ultimately only one decision which will be made by a unitary person or group of decision-makers in regard to that problem. The fact that the person or group may err does not mean that the decision was not a rational one at the time, for “time” is a great factor in how one (or several people) perceive(s) a problem.

Thus, though this writer believes that governmental problems and decision-making should be analyzed in terms of all three models interconnected (MII to MIII to MI), if one had to choose which model would be most useful in looking at events such as the CMC, MI would be chosen. Despite the difficulties posed by finding an acceptable definition of “rationality” and the effect which time has had on how one perceives a problem, MI has several points which make its use more desirable than MII or MIII regarding major problems or crises:

- With MI, “the intuitions and expectations of the average citizen” can be used to ask, “What would I do if I were the enemy?”

- Analytical and predictive international war games can be developed by “Think Tanks” through the use of MI better than through the use of MII or MIII. “The Rational Actor paradigm is functional in a practical analytic framework” for more situations – at times it is harder to weigh specific organizational and bureaucratic influences on certain problems and decisions.

- There is a broader range of interpretation possible with MI: action can be explained in terms of –

- a) the aims of the unitary national actor of government.

- b) a nation or national character (now Secretary of State Kissinger, who incidentally advocates “defining goals and priorities,” a characteristic of MI, once remarked that one should focus on the “national character, psychology, and preconceptions in explaining failure of American foreign policy.”

- c) an individual leader (President Lincoln when voting “aye” on an issue at a meeting once was voted down by all present, yet said, “The ‘ayes’ have it.” Or leadership clique.

4) most importantly, in dealing with situations involving nations like the Soviet Union, MI is far more useful in analyzing decision-making activities, simply because one cannot readily ascertain the effect of their internal organizations and bureaucracies upon their foreign policy.

Moreover, with respect to the specific crisis of Soviet missiles in Cuba, there were statements made which would tend to support the use of an MI framework of analysis over either MII or MIII:

- “Leaders in the White House talked directly with the commanders of the destroyers in the quarantined area.”

- President Kennedy, when he first learned of the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba, exclaimed in very personal terms, “He (Khrushchev) can’t do that to ME!”

- Robert Kennedy intimated that “if six of the members of the ExCom had been President, I think the world might have been blown up.”

Unfortunately, however, with regard to the CMC, none of Allison’s models provides a complete explanation of what occurred. For example. There is no examination in any of the models of all the hypotheses for why the Soviets finally decided to withdraw the missiles. In the author’s own words: “The full story of the withdrawal of Soviet missiles cannot be told: the information is simply not available.”

In the final analysis, it seems to this writer that the best picture of governmental decision-making cannot be obtained if one is limited to the use of a single model. Allison speculates at the end of the book that it might be beneficial to combine two or more of the models. Indeed, one is caused to wonder why he had not realized this earlier in reviewing his own remarks:

- “The presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba cannot be understood apart from the political leaders’ decision to direct Soviet organizations to install them.” (MI and MI)

- “The ExCom’s choice of the blockade cannot be understood apart from the context in which the necessity for choice arose.” (MI, MII, and MIII)

He even admitted at one point in his work that, in reality, not only do “analysts shift from variant to variant of a model,” but they also probably “deal with several models,” and that is the way it should be. Allison concluded that MI should be “supplemented by,” not “supplanted by” MII and MIII. Perhaps better arguments can be made for the use of MII or MIIII alone in non-crisis or less significant decision-making situations (If there is no crisis or important policy to be made, decision-making obviously can be delegated to individuals within an organizational or bureaucratic structure, but that fact does not justify an entire framework of analysis whereby decision-making is regarded solely in those terms). However, it is the opinion of this writer that all three models should be combined with MII serving as the foundation for MIII in which turn is the foundation for the MI – each perspective moving from general decision-making points to specific decision-making points, and from a large number of actors to an ever smaller number with the realization that the actors are conditioned by their perception of national ideology, personal, and political motives. What good then, one might ask, was Allison’s effort to develop three distinct methods whereby one might analyze the decision-making process within government? In addition to the “collective” use of the models described above, the most important use which can be made of these frameworks of analysis is in the area of “predicting futures” by their application to the development of international systems models. Therefore, Allison’s ESSENCE OF DECISION remains a valuable contribution in more ways than one to efforts being made to understand how American government works and in what ways it might be improved in the future.

In dealing with Vladimir Putin today, though, America cannot afford to be duped again by the “Russian Bear.”

We must remember the words of Rudyard Kipling in 1898: “When he shows at seeking quarter, with paws like hands in prayer, that is the time of peril – the time of the Truce of the Bear.”

© 2022 Dennis Cuddy – All Rights Reserved

E-Mail Dennis Cuddy: recordsrevealed@yahoo.com

By Dennis Cuddy, Ph.D.

By Dennis Cuddy, Ph.D. Alexander went marauding eastward from Macedonia, but he was also looking for the “secret knowledge” of the survivors of Atlantis (as did Heinrich Himmler). When he got to the wall surrounding India he met a superior army which repulsed Alexander, who was wounded and taken back to Macedonia. Rudyard Kipling was a member of the Rhodes Trust and spent a lot of time in India and wrote The Man Who Would Be King. The movie by that title starred Sean Connery and Michael Caine. (Kipling’s book in the 1890s had left angle Hindu swastikas on them). When the head of the monks (who were descended from the the original Aryans who were the only survivors of Atlantis) saw Connery and Caine, he was going to kill them until he saw a medallion around Connery’s neck and said it was just like the medallion Alexander the Great had given them thousands of years earlier.

Alexander went marauding eastward from Macedonia, but he was also looking for the “secret knowledge” of the survivors of Atlantis (as did Heinrich Himmler). When he got to the wall surrounding India he met a superior army which repulsed Alexander, who was wounded and taken back to Macedonia. Rudyard Kipling was a member of the Rhodes Trust and spent a lot of time in India and wrote The Man Who Would Be King. The movie by that title starred Sean Connery and Michael Caine. (Kipling’s book in the 1890s had left angle Hindu swastikas on them). When the head of the monks (who were descended from the the original Aryans who were the only survivors of Atlantis) saw Connery and Caine, he was going to kill them until he saw a medallion around Connery’s neck and said it was just like the medallion Alexander the Great had given them thousands of years earlier. milestone in the global fight against COVID-19 because it’s the first drug to demonstrate clinically and statistically meaningful reduction in deaths in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19.”

milestone in the global fight against COVID-19 because it’s the first drug to demonstrate clinically and statistically meaningful reduction in deaths in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19.” fun of him. These types of set-ups occurred again and again until the 2020 election, with a compliant press/media unwilling even to investigate how “Biden underperformed Hillary Clinton in every major metro area around the country, save for Milwaukee, Detroit, Atlanta and Philadelphia….In these big cities in swing states run by Democrats…the vote even exceeded the number of registered voters.” (Rasmussen Reports) Protests ensued, dividing the Republican Establishment and the Trumpists, culminating in the June 6, 2021 violence in Washington, DC.

fun of him. These types of set-ups occurred again and again until the 2020 election, with a compliant press/media unwilling even to investigate how “Biden underperformed Hillary Clinton in every major metro area around the country, save for Milwaukee, Detroit, Atlanta and Philadelphia….In these big cities in swing states run by Democrats…the vote even exceeded the number of registered voters.” (Rasmussen Reports) Protests ensued, dividing the Republican Establishment and the Trumpists, culminating in the June 6, 2021 violence in Washington, DC.

according to Time magazine reporter Robert Sherwood, the attack would occur within the first 10 days of December. The headline on THE HONOLULU ADVERTISER for November 30, 1941 read “Japanese May Strike Over Weekend.” (photo available)

according to Time magazine reporter Robert Sherwood, the attack would occur within the first 10 days of December. The headline on THE HONOLULU ADVERTISER for November 30, 1941 read “Japanese May Strike Over Weekend.” (photo available)

There were unique neighborhood characters like Kenneth who repaired watches for a living, but also made popsicles for the children and drove up to the little open air market in his jeep loaded with kids to get baseball cards and gum. He also taught us a baseball game played with cards for a hot or rainy day (turn over 3 cards and 2 of a kind was a single, three of a kind a triple, etc.). Another character was “Uncle John” who planted corn, etc., with a mule right there in the city. And there was a neighborhood leader, Mrs. Hawks, who occasionally got a permit from the city to block off the street for a block party where everyone would bring something to share with others (e.g., hot dogs, potato chips, etc. like in the original movie “The Sandlot”).

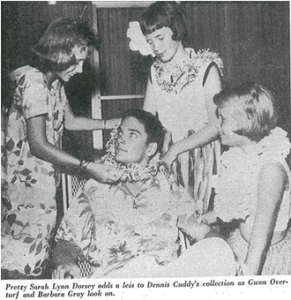

There were unique neighborhood characters like Kenneth who repaired watches for a living, but also made popsicles for the children and drove up to the little open air market in his jeep loaded with kids to get baseball cards and gum. He also taught us a baseball game played with cards for a hot or rainy day (turn over 3 cards and 2 of a kind was a single, three of a kind a triple, etc.). Another character was “Uncle John” who planted corn, etc., with a mule right there in the city. And there was a neighborhood leader, Mrs. Hawks, who occasionally got a permit from the city to block off the street for a block party where everyone would bring something to share with others (e.g., hot dogs, potato chips, etc. like in the original movie “The Sandlot”). romantically dance together, boys with girls, after our parents had paid to give us ballroom dance lessons. (Three photos of Dennis Cuddy at 14 years old in 1960 can be seen here.)

romantically dance together, boys with girls, after our parents had paid to give us ballroom dance lessons. (Three photos of Dennis Cuddy at 14 years old in 1960 can be seen here.) the quickening of the tempo of human life described in Orwell’s futuristic novel titled 1984, the fractious anapestic rhythm of rock music planned by Theodor Adorno of the Frankfurt School, and the psychological manipulation of Edward Bernays in his 1928 book PROPAGANDA and Bertrand Russell in his 1951 book, THE IMPACT OF SCIENCE UPON SOCIETY. Schools began to undermine parental values by teaching students situation ethics via values clarification techniques like “The Lifeboat game” where they would decide who lives and dies.

the quickening of the tempo of human life described in Orwell’s futuristic novel titled 1984, the fractious anapestic rhythm of rock music planned by Theodor Adorno of the Frankfurt School, and the psychological manipulation of Edward Bernays in his 1928 book PROPAGANDA and Bertrand Russell in his 1951 book, THE IMPACT OF SCIENCE UPON SOCIETY. Schools began to undermine parental values by teaching students situation ethics via values clarification techniques like “The Lifeboat game” where they would decide who lives and dies.